Home, Haven, Hope

A loving home.

A safe space to learn.

At Action Cambodge Handicap,

young Cambodians with disabilities

have a chance to bloom.

Action Cambodge Handicap (ACH) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, offers a safe place and community for individuals living with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Founded in 2012, it houses about 15 residents at a time, teaching them life skills and providing socio-emotional support .

Unseen, uncared for

Figures on how many people have disabilities in Cambodia, a country of 16 million people, vary widely.

Official figures range between 1.44 to 4 per cent, while another estimate states that about 10 per cent of the population aged five years and older have some form of disability.

Both are below the World Health Organization’s global prevalence rate of 15 per cent, and disability sector experts in Cambodia believe the country’s numbers are much higher.

People with disabilities in Cambodia are excluded from society, lacking access to medical and rehabilitative services, and opportunities for education and work. They also face discrimination, while poor infrastructure creates obstacles for people with mobility problems.

"The parents often assume their kids [with disabilities] can't do anything. We have had individuals in their 30s, who have never done anything in their lives."

32-year-old Srey Noun is the life of ACH with her sweet demeanor and generous spirit.

Born with Down syndrome, she was often mistreated and abused by the people around her. She has no family, but now calls the ACH community her adopted family.

"I was so excited [because] I heard that I can work, earn money, [and] buy things for myself."

Before she arrived at ACH, Srey Noun stayed at another NGO shelter, but shared that she “did nothing, [only] hang out, and sleep.”

At ACH, she has learnt how to make jam for sale, such as how to prepare the pineapples, and she hopes to eventually learn how to make the jam itself. She also recently landed a part-time job working as a cleaner at a restaurant, on a trial basis.

"I love working," she says.

ACH staff live together with the youths at the organisation’s premises so that the youths can experience a healthy family environment.

Among them is Srey Tun, with Srey Noun looking over her shoulder, who manages the operations at ACH's jam factory, and also plays the role of a parental figure and confidante.

25-year-old Panh sits by the window, occasionally helping to label the jam jars. The jam factory offers a place where vulnerable adults or those with limited abilities can engage in tasks adapted for them so that they can carve out a livelihood.

Every youth has a unique place in the community and nobody is left out, regardless of ability.

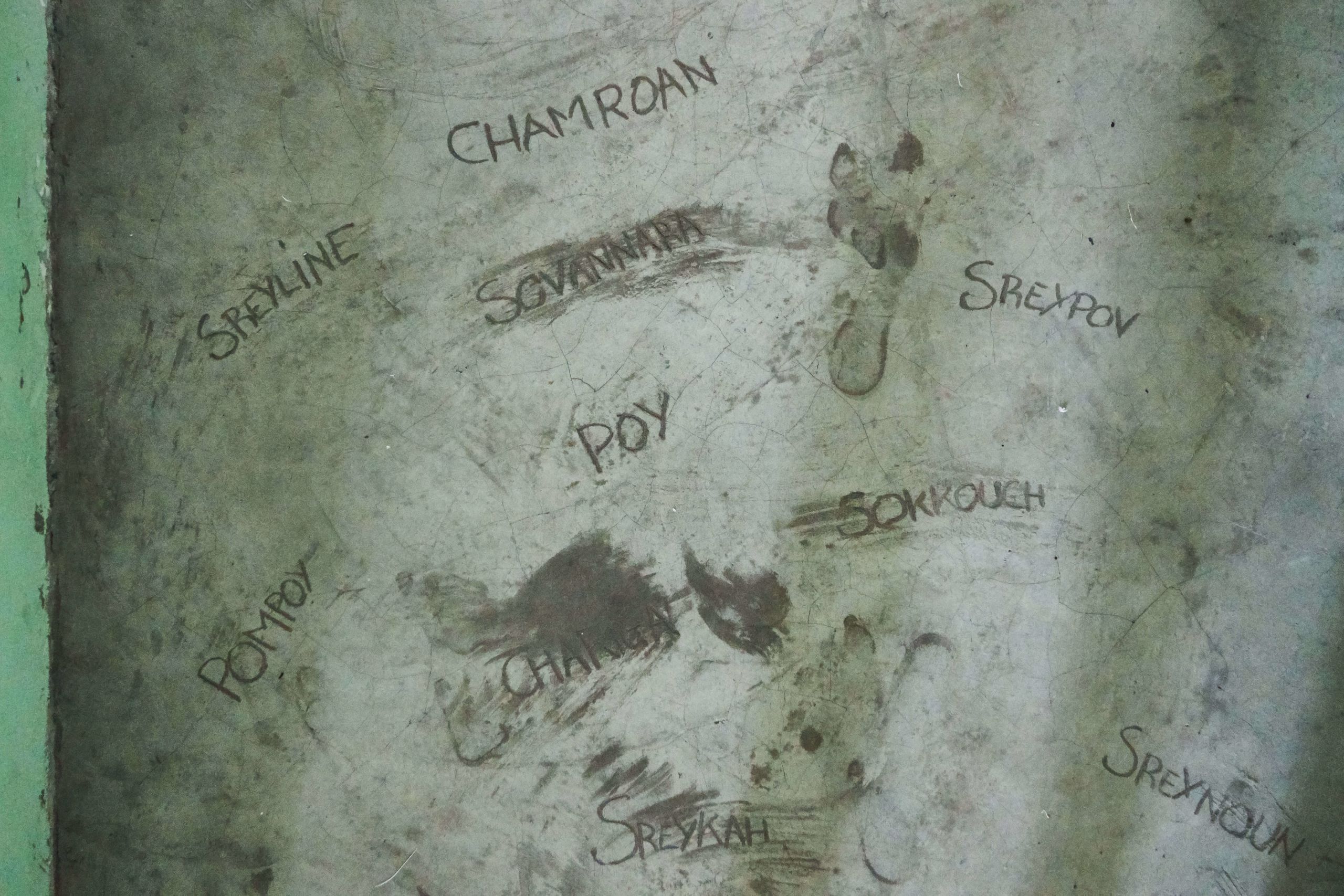

Inscribed on the concrete floor of the jam factory are the names of the all the youth.

Jam-making provides a source of income for ACH and the youths, helping to subsidise daily living expenses. The jams come in different flavours and are sold all over Phnom Penh and Siem Reap.

At the moment, income from jam-making supports only 30 per cent of ACH’s costs, and the organisation relies on donations. The expenses for caring for each youth add up to US$120 to $150 a month.

ACH also pays the youth working in its factory about US$1 a day.

This may not sound like much, but according to a 2014 Asian Development Bank report, 41 per cent of the Cambodian population live on less than US$2 a day. There is a mandated minimum wage of US$190 a month, but it only applies to workers in the garment, textile and footwear industry.

Sephan notes that the US$20 the youth receive each month is entirely theirs to spend; ACH takes care of their shelter, clothing, meals, recreation, education and any other needs.

To become less reliant on donations and create more work opportunities for its youth, ACH is raising funds to open a cafe in Phnom Penh.

"The stereotype is that [people with disabilities] have no ability. We want to engage them. If you spend the time nurturing them from a young age, they can grow up and take care of themselves."

Despite the tough responsibility of managing the organisation, Sephan (above, sitting on the ledge) shares that she finds great joy learning from the youths, especially with their purity of heart.

She says, "Our tenet is, 'Take care of yourself, and everything else can thrive.'"

ACH believes that every individual is capable of being independent.

Toothbrushes at the common wash area are labelled with pictures to train the youths to build a healthy routine and learn to care for themselves.

The youth also learn cooking and food preparation skills, and take turns to whip up daily meals with guidance from ACH staff.

ACH believes in helping each individual find work to support themselves if they are able. So far, it has supported over 20 youth to lead independent lives, working as security guards, cleaners and doormen.

Among them is Sok Khuoch, 26, who works at a nearby charcoal factory, a job he landed upon ACH’s recommendation.

Sok Khuoch (in black) continues to live at ACH as his family environment at home has been unstable.

Aside from trying to set aside savings, he sometimes uses his wages to buy treats for his ACH family.

Sovannara, 25, lived at ACH for nine years before moving back to live with his family, after finding employment as a security guard.

He shares, “I feel relieved to earn some money for myself and my family. It’s a very rewarding feeling.”

23-year-old Chamroan (right) has also moved out of ACH, after he found work at a hotel. He met his life partner who also lives with an intellectual disability, through an NGO programme.

Twice a week, ACH works with partner organisations to organise rugby and skateboarding sessions for the youths.

These activities help build teamwork, and provide an outlet for the youths to relax and have fun outside of the home.

Srey Noun guiding her friend Chariya as she learns a new move on the skateboard. Srey Noun loves skateboarding, and shares that “I’m never scared. I wear good shoes.”

She adds, “I see myself as a big sister. I look out for my friends.”

A favourite past-time among the youths is karaoke and dancing. Sok Khuoch tries to take the microphone from Srey Pov when his favourite song comes on the playlist.

The evenings at ACH are a special time when the youths turn on their favourite music and dance freely amongst themselves. Everyone is present in the moment, and a sense of pure joy and carefreeness is palpable.

Whilst mental disability remains a stigma in mainstream society, ACH offers a place where these persons are accepted, and can thrive as unique, productive individuals.

Donate to Action Cambodge Handicap, and give youth with disabilities a chance to lead independent lives.

If you hold a Singapore-issued credit card, click the button below to find out how you can donate.

If you are in Phnom Penh or Siem Reap, visit these stores to buy their jam.

CONTRIBUTORS

Grace Baey

Photographer

Lin Yanqin

Producer and Content Designer

Sharon Pereira

Executive Producer