From fleeing for their lives, to finding peace of mind

Health Equity Initiatives is helping refugees in Malaysia find the mental well-being and resilience they need to survive

Sara

Volunteer at Health Equity Initiatives and refugee

A COMMUNITY GATHERS

They might talk about the struggle to make ends meet in a country in which they are not allowed to work legally.

Or they might share a memory of home, which they were forced to flee.

Or they might voice their ever-present anxiety of wondering if they will ever be resettled in a country where they can live, work and play as citizens.

These are stories that Sara [not her real name] has heard many times.

As a volunteer Community Health Worker for Health Equity Initiatives, a Malaysian non-profit, Sara helps out at such group support sessions, which helps refugees learn about their mental health needs, and how to cope.

Having fled from Afghanistan to Malaysia in 2014, Sara understands all too well how the participants feel.

A FLIGHT TO SAFETY

When the Taliban came knocking, Sara and her husband knew it was time to leave.

Her husband, whose job involved transporting oil, had been picked up by Taliban forces and told he had to work for them, or risk his family's safety.

"They threatened him, [saying] that they know our address and also the family, and they will do whatever they want," recalls Sara. "When my husband came back home, he was very anxious and very distressed, and told me and [his parents] to escape from the village."

His parents however, refused to flee, believing their son was the target, not them. Before they parted ways, Sara's mother-in-law gave her grandson, who was just eight months old at the time, a rosary.

"She put it on my son's neck and said, 'God bless you and God protect you. And wherever you go, just pray to God.'"

Later, when Sara and her husband reached Kabul, they learnt that back in their village, her husband's parents had been shot in their home by gunmen.

For Sara, the rosary brings back feelings of grief, but is also a reminder of home, and that she is not alone.

"It gives me motivation to continue my life, especially to fight for my kids. Because although we lost our mother-in-law and father-in-law, we didn't lose our hope. We didn’t lose our resilience."

These thoughts fuel Sara when she encounters refugees like herself who have experienced trauma. "I try to motivate them, try to empower and encourage them. And also mostly I try to let them know that there is a God, who is the witness and who will help us," she says.

Sara's home in Malaysia. [Photos by Sara]

![Sara's home in Malaysia. [Photo by Sara]](./assets/rnstkoi9dV/s_01-1000x750.jpeg)

Malaysia is currently host to some 177,800 refugees and asylum seekers, providing a transitory home as they seeking safe resettlement in a third country. In Southeast Asia, only Thailand hosts more displaced persons (573,518 including stateless persons).

Refugees and asylum seekers usually arrive bearing trauma from the persecution and conflict they experienced in their home countries.

In addition, they are grappling with being separated from loved ones, coping in their host country, and face constant and tremendous anxiety regarding their well-being and future.

Yet their mental health - essential to the survival of all human beings - is usually overlooked amid other needs.

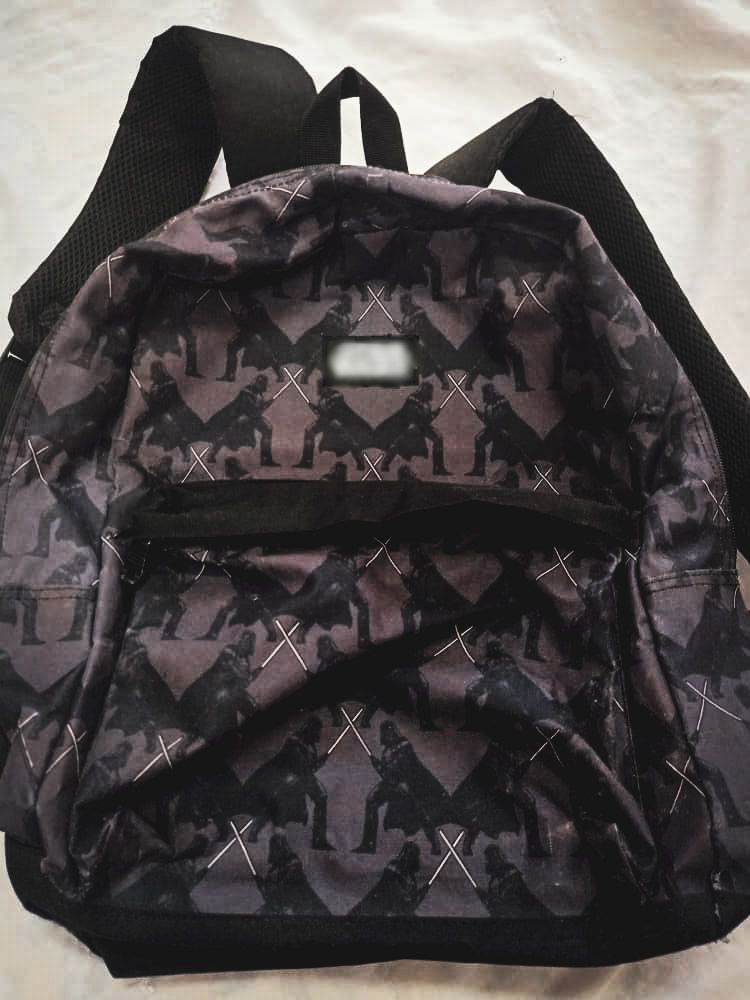

A LIFE PACKED INTO A SINGLE BAG

The backpack containing all of Sara and her family's belongings when they arrived in Malaysia. [Photo by Sara]

The backpack containing all of Sara and her family's belongings when they arrived in Malaysia. [Photo by Sara]

When Sara and her family arrived in Malaysia, they only had a backpack containing cotton diapers and milk for her baby, and a set of clothes each for her and her husband.

"It was all the things that we had, because we couldn't bring much, we couldn't do much. And the memory that we have from our home country is in this bag, that contained uncertainty, fear and difficulty."

Sara recalls her first few days in Malaysia.

In Malaysia, a group of NGOs have emerged to support refugees' mental health, among them A Call To Serve, Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation, Malaysia Social Research Institute, and Health Equity Initiatives (HEI).

These organisations offer much-needed services in counselling, psychotherapy and referral psychiatric care, which are usually out of reach for refugees due to cost, the fear of being detained and deported, and being stigmatised.

HEI was the first NGO in Malaysia to offer community-based mental services for refugees. For Sara, and many others, crossing paths with HEI has been a turning point.

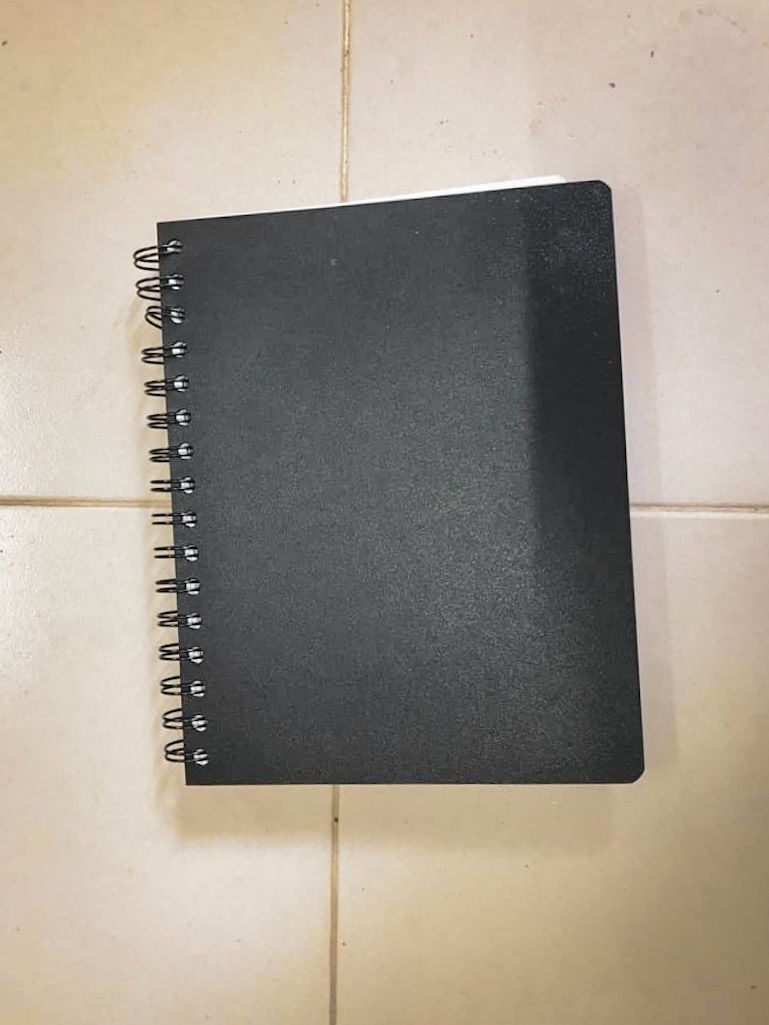

THE STORY OF A NOTEBOOK

Hicheal's journal containing his experiences back home in Myanmar, where he experienced persecution and discrimination as Rohingya. [Photo by Hicheal]

Hicheal's journal containing his experiences back home in Myanmar, where he experienced persecution and discrimination as Rohingya. [Photo by Hicheal]

Having to apply for a travel permit just to leave his village for the nearest township. Being arrested and detained for offences he did not commit. Not being able to marry without permission from local authorities and paying them large sums of money.

These are among the memories of being persecuted as a Rohingya in Myanmar, bound in Hicheal's notebook, an item he could not leave behind when he left Myanmar.

"I recorded a lot of things on this book. When I see this notebook, I remember everything," says Hicheal [not his real name].

In Myanmar, Hicheal was an interpreter for an NGO, and was viewed suspiciously by local authorities. Once, he was detained for 35 days after being falsely accused of using a SIM card from another country.

"They arrested another guy at the same time with me. They released me because I paid US$5,000 for my release. The other guy, he was not able to pay that kind of money. They sent him to prison for one year."

Fearing for his safety, Hicheal left Myanmar for Malaysia in hopes of seeking asylum and settling permanently in another country.

The journey was a dangerous one. Travelling by boat for seven days, he and the other passengers were not given food, leaving them half-starved.

At one point he was beaten and held ransom for additional money by the agent who arranged his journey.

"My parents sent money, but the agent did not believe me and then start beating me. And then I got injured in my body. I'm still feeling pain on my body because I was beaten by the agent. I could not forget this journey forever."

Arriving in Malaysia in 2013, Hicheal found that despite his education and experience in Myanmar, he could not find a job to support him and his family.

Refugees in Malaysia are not allowed to work legally, and many turn to odd jobs, which leave them vulnerable to exploitation. And because refugees in Malaysia are considered illegal immigrants, Hicheal worries that he may be detained and repatriated.

More recently, anti-refugee sentiment has been on the rise, creating even more fear among refugee communities.

Through a Rohingya community leader, Hicheal learnt that HEI was looking for volunteer Community Health Workers, and decided to apply and put his skills to use.

Everyday items on Hicheal's flat in Kuala Lumpur, where he lives with his family. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

Everyday items on Hicheal's flat in Kuala Lumpur, where he lives with his family. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

Outside Hichael's flat in Kuala Lumpur. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

Outside Hichael's flat in Kuala Lumpur. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

HEI: A BRIDGE TO MENTAL WELLNESS

A counsellor on the phone at HEI's office in Malaysia, and consultation rooms for HEI's patients. [Video and photo by Amin Kamrani]

A counsellor on the phone at HEI's office in Malaysia, and consultation rooms for HEI's patients. [Video and photo by Amin Kamrani]

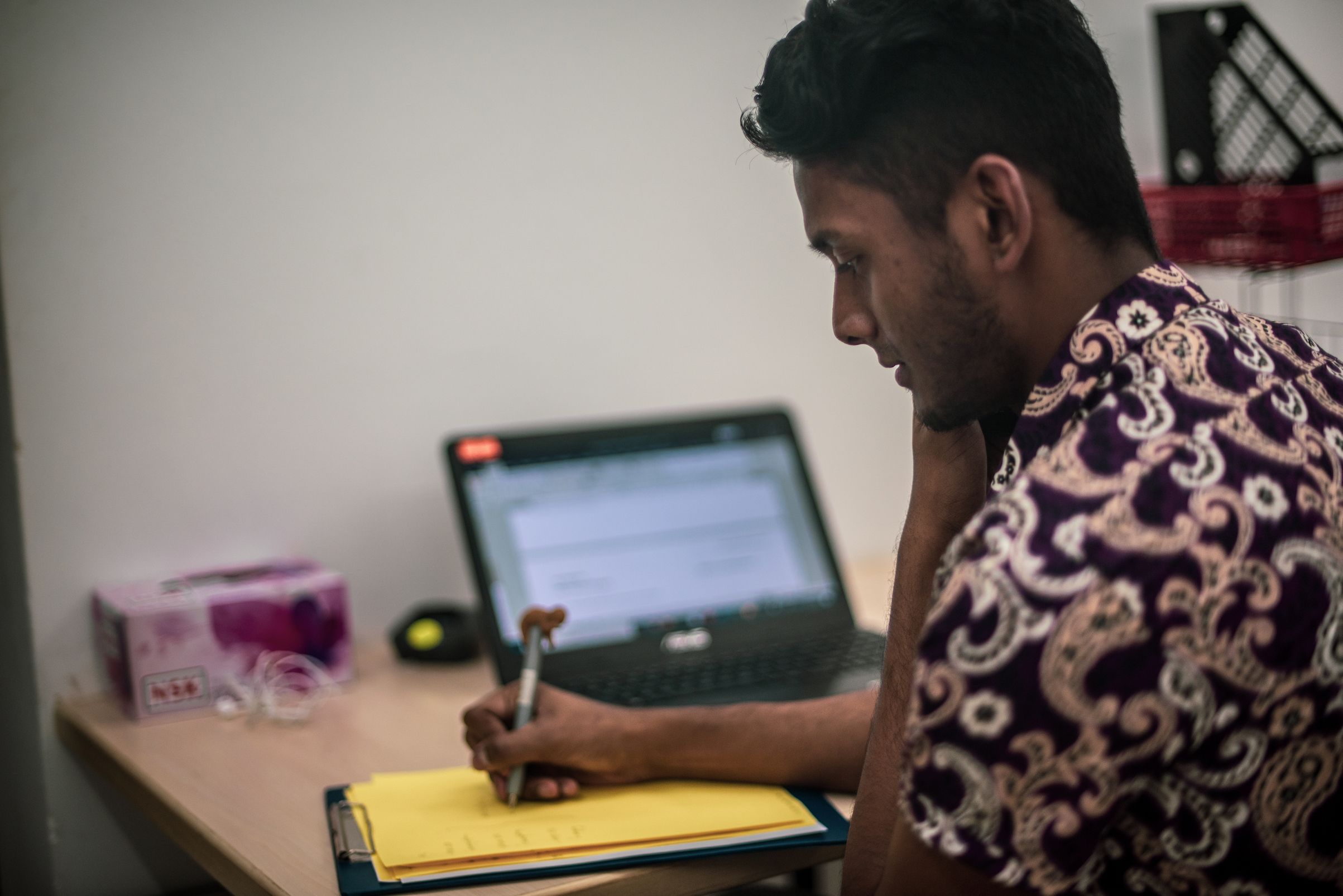

A psychosocial support officer at the HEI office. HEI's counsellors, clinical psychologists, psychosocial support officers and patient managers support some 400 patients. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

A psychosocial support officer at the HEI office. HEI's counsellors, clinical psychologists, psychosocial support officers and patient managers support some 400 patients. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

A play area for participants' children at the HEI office. HEI also offers rehabilitation or daycare for some patients. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

A play area for participants' children at the HEI office. HEI also offers rehabilitation or daycare for some patients. [Photo by Amin Kamrani]

HEI was started in 2007 by Dr Sharuna Verghis and Dr Xavier Vincent Pereira, who saw that the mental health of marginalised communities in Malaysia was severely stressed because of their circumstances.

Under HEI, they began providing mental health treatment, as well as empowering communities to create mental health awareness and support, by training refugees to volunteer as Community Health Workers (CHWs). To date, it has trained over 300 CHWs.

Patients are introduced to HEI through referrals by UNHCR and other NGOs. HEI has also worked with UNHCR to build capacity in this field through workshops. It is funded through grants and donations.

NUMBER OF PATIENTS SERVED BY HEI

350-400

TYPES OF CASES SEEN

Anxiety

Depression

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Schizophrenia

“When I sleep it doesn’t feel like sleep, and everything I have experienced comes to my head.”

Min, a refugee forced to work on a plantation

Read more witness accounts on HEI's website

As CHWs, Sara and Hicheal are a bridge between HEI and the various refugee communities living in Malaysia's Klang Valley.

CHWs undergo nine months' training, after which they can help identify signs and symptoms of mental health problems, make referrals for mental health and psychosocial interventions, and translate for therapy.

They also conduct outreach, education and mental health screenings within their respective communities.

"I wanted to be a CHW, because I wanted to help my community through HEI. They have been facing problems, because of stress or worry...because of financial issues and the current state of Malaysia, especially for their ethnicity. I could help my community, as well as patients."

FINDING STRENGTH IN OTHERS, AND IN THEMSELVES

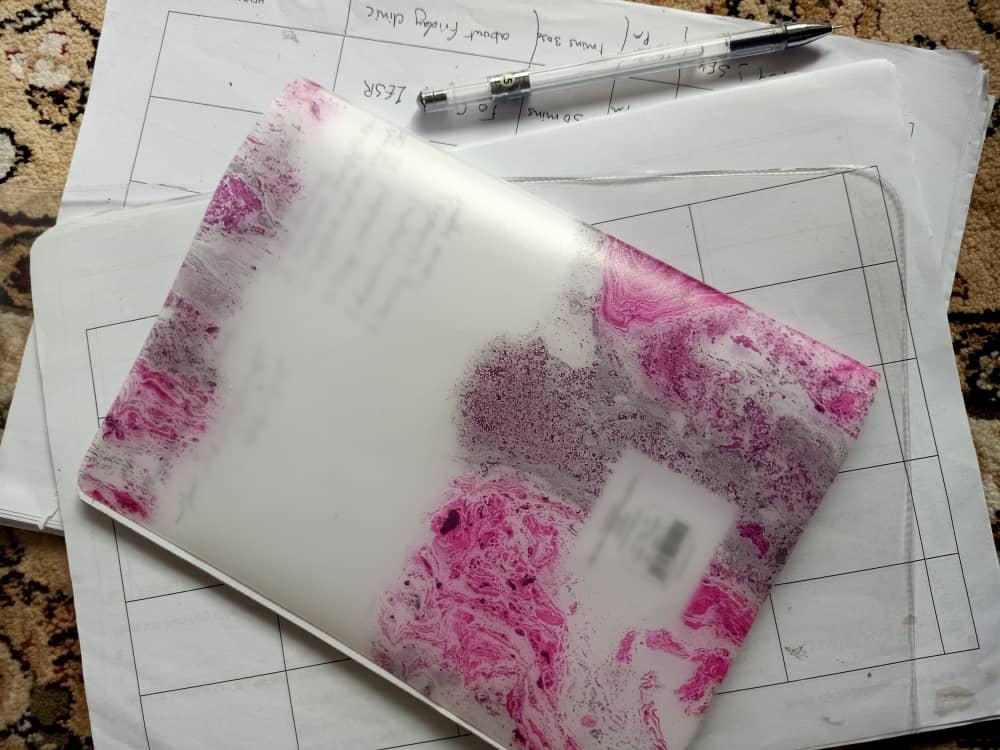

A notebook used by Sara for her work as a CHW. [Photo by Sara]

A notebook used by Sara for her work as a CHW. [Photo by Sara]

CHWs like Sara and Hicheal support HEI's services, but they are also a focal point for their community in times of need, be it trouble paying for rent and food, or seeking healthcare - problems that have escalated amid the COVID-19 pandemic, as odd jobs dry up.

"We receive calls at night, even during weekends. It is my honour to be supportive to my community, give them information about NGOs or organisations [that can help them] and mentally support them, because sometimes they just need to talk, and even listening to somebody can be a help."

A key part of being a CHW is teaching their communities how to recognise signs of stress and how to cope.

"Being a refugee makes you very vulnerable. When you are mentally strong and have coping strategies, and also [when] you realise what is your mental health issue, it can help you find a way to reduce the symptoms," says Sara.

Most of the refugees she encounters have symptoms of depression and anxiety from the stress of being in exile; symptoms Sara has learnt to spot in herself.

"I am afraid that if I am forced to go back to my country, I fear that every one of us will die, and that is very scary, not just for myself, but for my kids."

Another fear is uncertainty, "because you don't know how long you will be in Malaysia, with all the difficulties or challenges that you're suffering."

To cope, Sara does relaxation exercises she has learnt from HEI like deep breathing, to focus on "beautiful and positive" things, like talking to a friend or watching a movie.

She is also encouraged by the empowerment and opportunity to learn from her work as CHW for HEI. For example, HEI organises case-based learning sessions regularly where CHWs can learn about different psychology topics.

"For me that is like a big opportunity, that I can be a part of that class, because for me as a refugee, that is something impossible, joining a university. But HEI provides me such opportunities," says Sara.

As Malaysia entered lockdown under its Movement Control Order (MCO) to stem COVID-19's spread, refugees saw their limited means of making ends meet dry up, and many struggle to pay rent and buy food.

Meanwhile, tensions rose over the presence of refugees in the country. A series of detentions saw refugees brought to crowded detention centres, and outbreaks have emerged.

Throughout all this, HEI has continued to facilitate safe access to healthcare for its community members. It has arranged transport to hospitals for treatments, and provides support and counselling over online platforms and phone calls where possible.

It also created information booklets in seven languages - from Arabic to Urdu - to educate refugees about how to stay safe and self-quarantine amid the pandemic.

BUILDING RESILIENCE, CREATING ACCEPTANCE

Sara and Hicheal are well aware of the tension over the presence of refugees in Malaysia, and hope to create more understanding of their circumstances.

Sara says that most Malaysians she encounters assume that she chose to migrate to Malaysia. "I try to explain that we are refugees, we were forced to run from our country. But we cannot make them understand that it is very difficult and it takes time [to be resettled]."

Adds Hicheal, "I came to Malaysia because it is a Muslim country...I came here not to stay permanently. I'm just here to save my life, as I can't stay in my country."

Their work as CHWs for HEI is essential to helping refugees cope and even thrive. As Sara puts it: "I believe that when a person is mentally and physically healthy, they will be able to support and help other community members."

Her goal, she says, is "living in peace and kindness and respect to Malaysians", adding, "I appreciate all of their kindness towards us."

Help HEI continue their work by making a donation

LET'S TALK ABOUT IT:

How can we encourage refugees to stay resilient amid the challenges they face in seeking asylum? Share your ideas on our forum.

This story is part of Refugees: Displaced not Discouraged, a series by Our Better World on the refugee issues, where you can discover more stories and ways to take action.

Here are a few of our stories from the series:

In Malaysia, a Refugee Community that Keeps Giving

From the heart of one refugee community to the heart of its host

From the heart of one refugee community to the heart of its host

Paths to an open future for refugees

Singapore doesn't accept refugees. Yet, as these Singaporeans show, not only is it a cause closer to home than one might think, but support can happen in many forms

Singapore doesn't accept refugees. Yet, as these Singaporeans show, not only is it a cause closer to home than one might think, but support can happen in many forms

The refugee crisis isn't going away. You can help

A refugee’s problems can’t be solved overnight. But here are some groups helping them get back on their feet, for a start.

A refugee’s problems can’t be solved overnight. But here are some groups helping them get back on their feet, for a start.

A school for refugees, by refugees

Stuck in a foreign land with few resources, these refugees in Indonesia didn't wait for a solution, they created their own.

Over on our Community Blog, refugees and their advocates share their journeys and perspectives in their own words:

The man from everywhere and nowhere

Allies in writing: Refugees shaping their own stories

A choice of sacrifice. A choice of hope

When you help a refugee, you help a neighbour

Education for refugees: Lessons from the ground

The refugee entrepreneur: HELPing those in need

Want to dive deep into mental health issues and how they affect all human beings? Explore through our stories and resources in our series, Silent no more: Giving voice to mental illness.

CONTRIBUTORS

Lin Yanqin

Producer, Writer and Content Designer

Amin Kamrani

Photographer

Sara and Hicheal

Photographs

Sharon Pereira

Executive Producer

Our Better World is the digital storytelling initiative of the Singapore International Foundation, which brings world communities together to do good.