Living with suicide

Five individuals share their deeply personal experiences with having attempted suicide, and how they continue to grapple with thoughts of ending their lives, having chosen to live despite their daily struggles.

Content warning:

This contains sensitive content on suicide which some people may find distressing.

“No man ever threw away life while it was worth keeping.”

The moments before and after

Each survivor describes the moments leading up to and after their suicide attempt.

Almost a third of a lifetime away, 59-year-old Mahita Vas recalls the day that might have been her last. A confluence of factors, including insomnia, parental duties and a recent diagnosis of Type 1 bipolar disorder, had pushed her to the edge. Overwhelmed and feeling helpless, she had thought, “You know what, I don’t need this,” deciding then, “I am done. I quit. I am checking out.”

In 2005, having contemplated suicide many times before, Mahita made up her mind.

Her husband, a recently retired pilot, was away. After putting her twin daughters to bed, she wrote farewell notes to each of them and her husband, asking them to forgive her. She also penned messages to a handful of close friends and colleagues, and called her late mother, who lived in the United States.

Then, Mahita went into the guest room, barricaded the door, and swallowed what sleeping pills she had left. But knowing that the pills would not be enough to kill her, she prepared a way to suffocate to death, before laying on the floor to await her last breath.

WATCH: Mahita and Mano talk about their brush with suicide.

Under the influence of psychosis

Driven by a psychotic episode at age 27, Muhammad Nur, aka ‘Mano’, was convinced that people were hunting him down to kill him. Paranoid and confused, he sought death as a way to escape his imagined assassins.

His mother was able to stop him from harming himself further. He was then admitted into the psychiatric ward at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) for 44 days.

While institutionalised, the case manager had assured him that if he could prove that people were out to harm him, she would help him. If not, then it was “all inside my mind”.

“I spent the afternoon going through the so-called proof,” says Mano. “After evaluating them, I noticed that this is not right. I just snapped out of it, like a light bulb [was switched on in my head]... I'm very grateful for that.”

Like Mahita and Mano, Jolyn, Nicole and Shafiqah all shared the same goal; to end their lives.

In telling their stories, each individual revealed a complex and unique web of trauma and circumstance that ultimately led to their decision to kill themselves.

Feeling unwanted and worthless

Growing up, Shafiqah Ramani and Jolyn Yong shared one thing in common; they both felt unloved, uncared for, and like outcasts.

As the only child until she was five years old, Shafiqah started to believe that her parents no longer wanted her when her siblings were born. And at nine years old, suicidal thoughts began to percolate in her mind, as feelings of being a “burden” to her family took hold.

By the time she turned 11, Shafiqah had started wondering whether life was worth living. One day, at home and feeling miserable she snapped and, on impulse, slit her wrists.

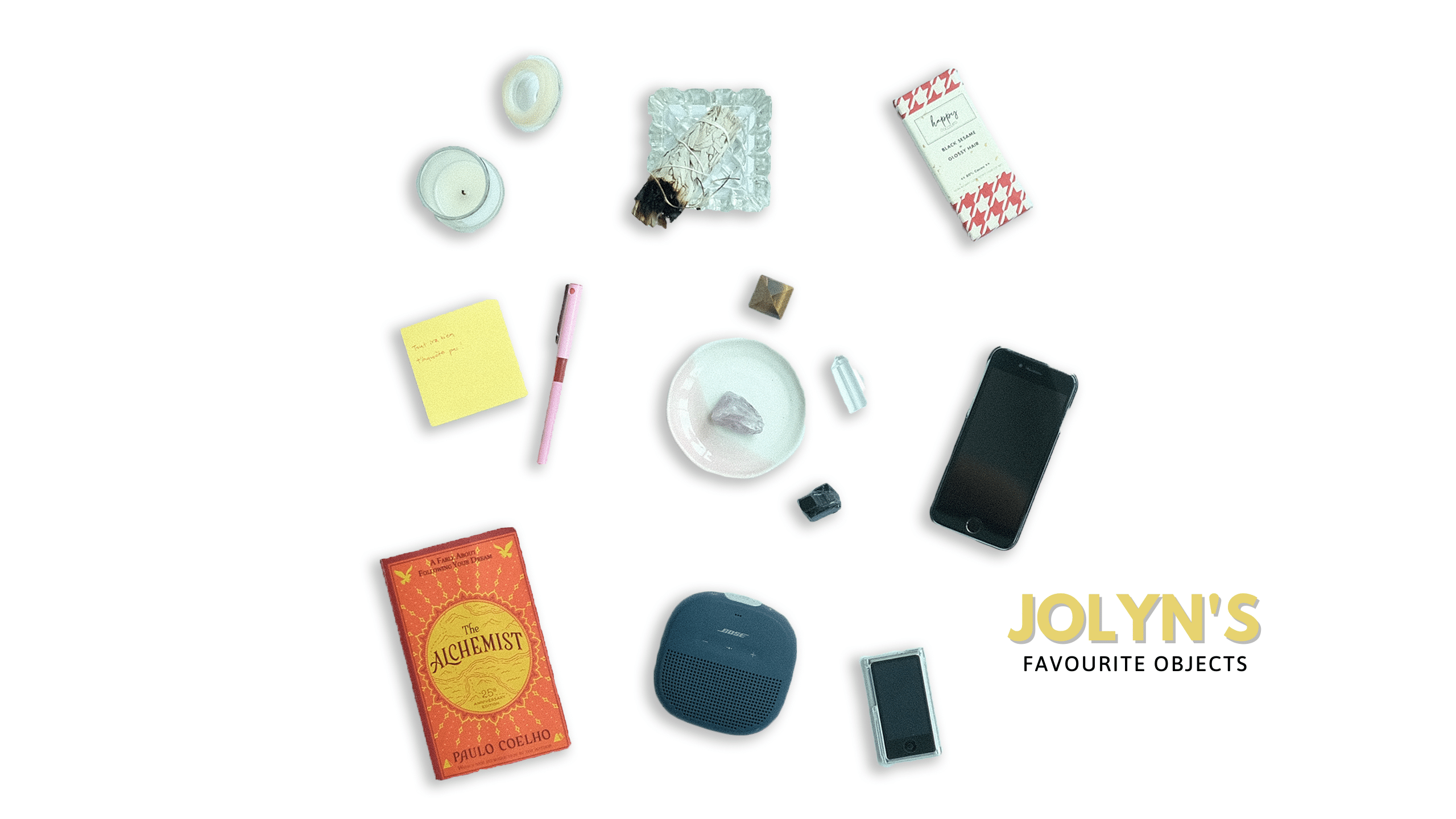

While Jolyn had always felt different, her fatalistic attitude only found a foothold upon returning to Singapore from Australia in 2019, after living there for a year. A stranger in her country, she had trouble adapting to life back home.

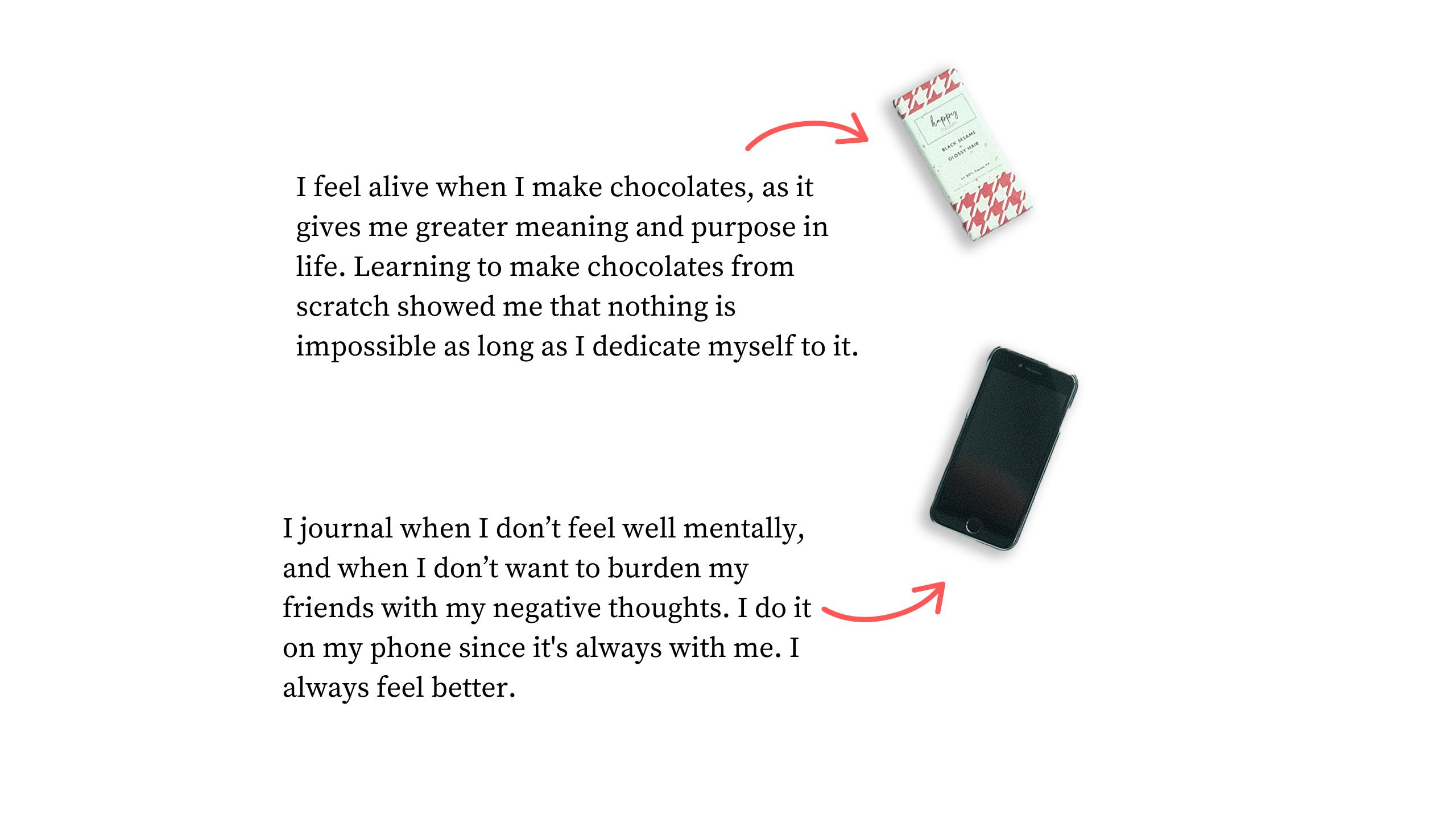

Having fallen out with her parents, she moved to her brother and sister-in-law’s, where a growing tension ensued. There was also the added stress of having started a new business making artisan chocolates.

Upset and feeling depressed, she contemplated jumping to her death 12 storeys up on the window ledge at her brother’s apartment. As Jolyn sat looking down into oblivion, a sense of calm fell over her. And if not for her sister-in-law returning at that point, things might have turned out differently.

WATCH: Shafiqah and Jolyn talk about their first suicide attempt.

Stalked and desperate

Having moved to Singapore alone at 16 years old, Malaysian Nicole Voon, 25, had a problem she could not shake off – a stalker who had been harassing and hounding her 24/7 for two years: “It was mentally, physically, emotionally draining… I even went back to Malaysia and it didn't stop,” she says. “My family was not helping, they were blaming me for what happened.”

Already feeling miserable and suicidal since she was 14, Nicole decided she would take her life in 2018, believing that it was the only way to stop her suffering.

“I was at my lowest. I wasn't doing well at work, or with my family, or in my relationship. I [felt like] a burden to everyone,” she says.

Read instead

She sought advice from a group of friends who were “in the same boat”: “They were telling me how many sleeping pills to take, what brand and what dose would work.”

Nicole took the pills and went to bed, not expecting to be alive by the morning. But fate had other plans for her.

“I felt very disappointed that I woke up. I was mad at my friends… ‘You told me this dose was good enough. Why did I wake up?’ Then I was questioning God, ‘What more is there to life?’”

Nicole Voon, 25, Business Owner

Nicole Voon, 25, Business Owner

Jolyn Yong, 29, Chocolate Maker

Jolyn Yong, 29, Chocolate Maker

Shafiqah Ramani, 28, Co-founder, Psychkick

Shafiqah Ramani, 28, Co-founder, Psychkick

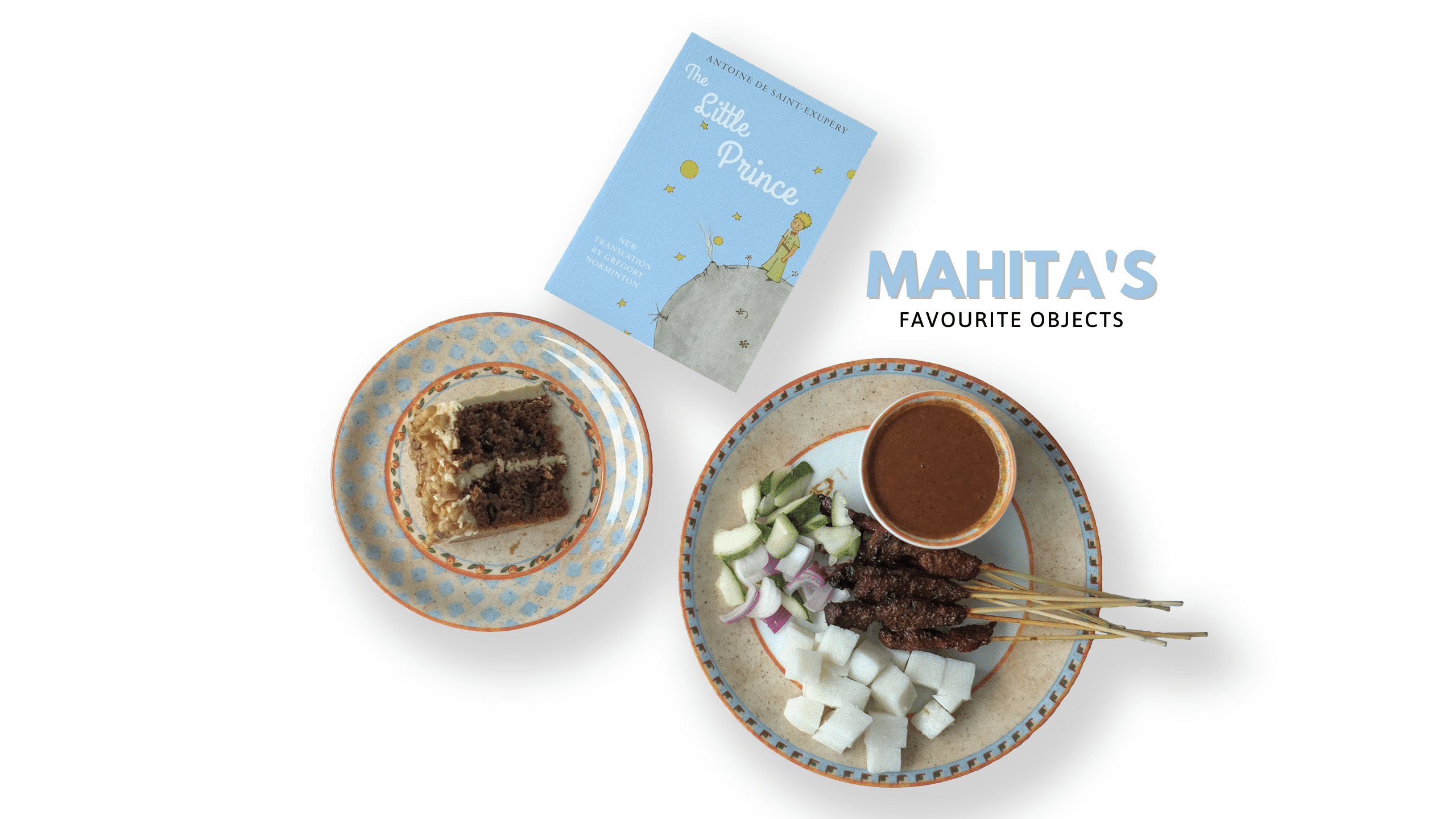

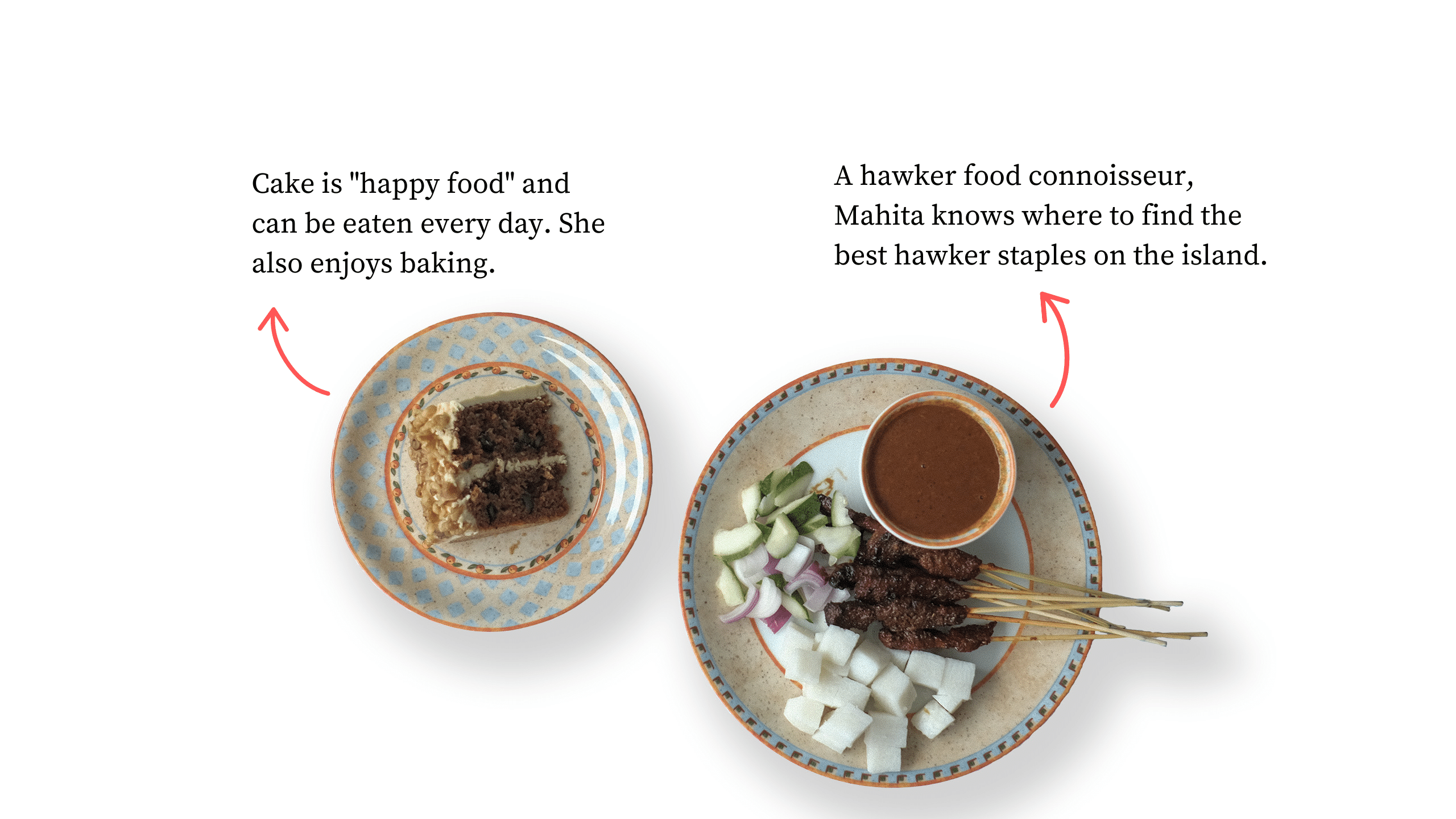

Mahita Vas, 59, Author and Homemaker

Mahita Vas, 59, Author and Homemaker

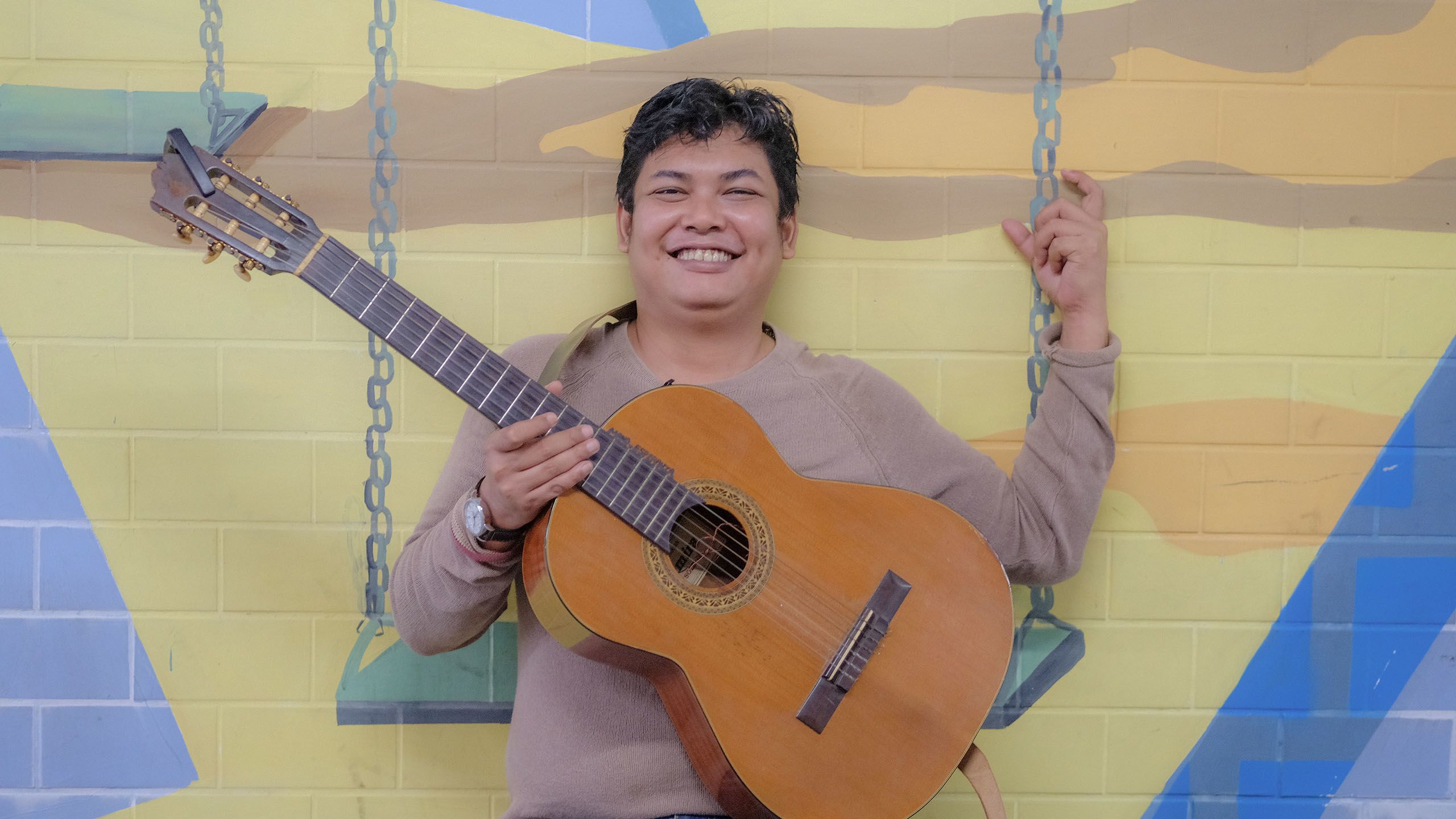

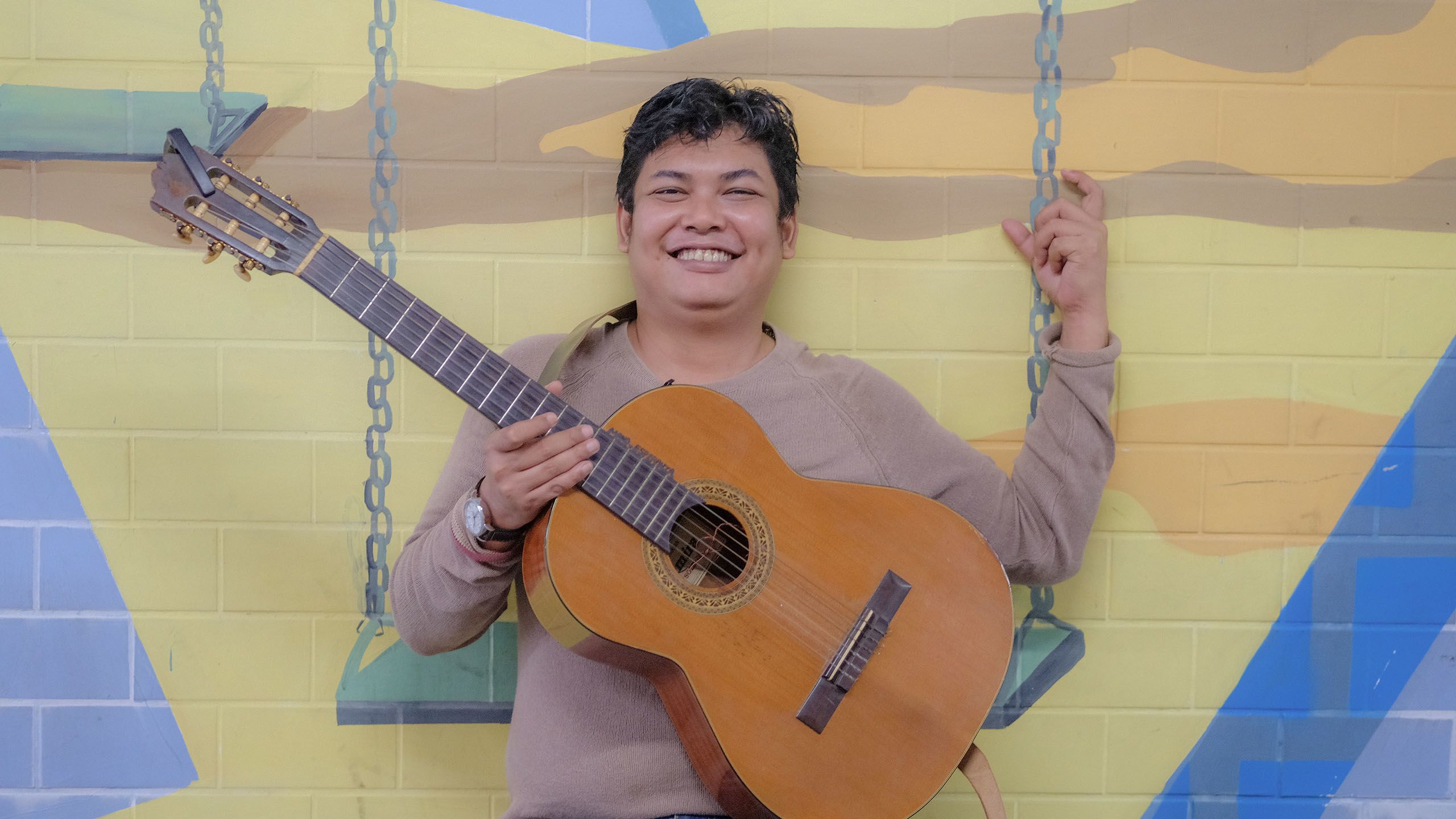

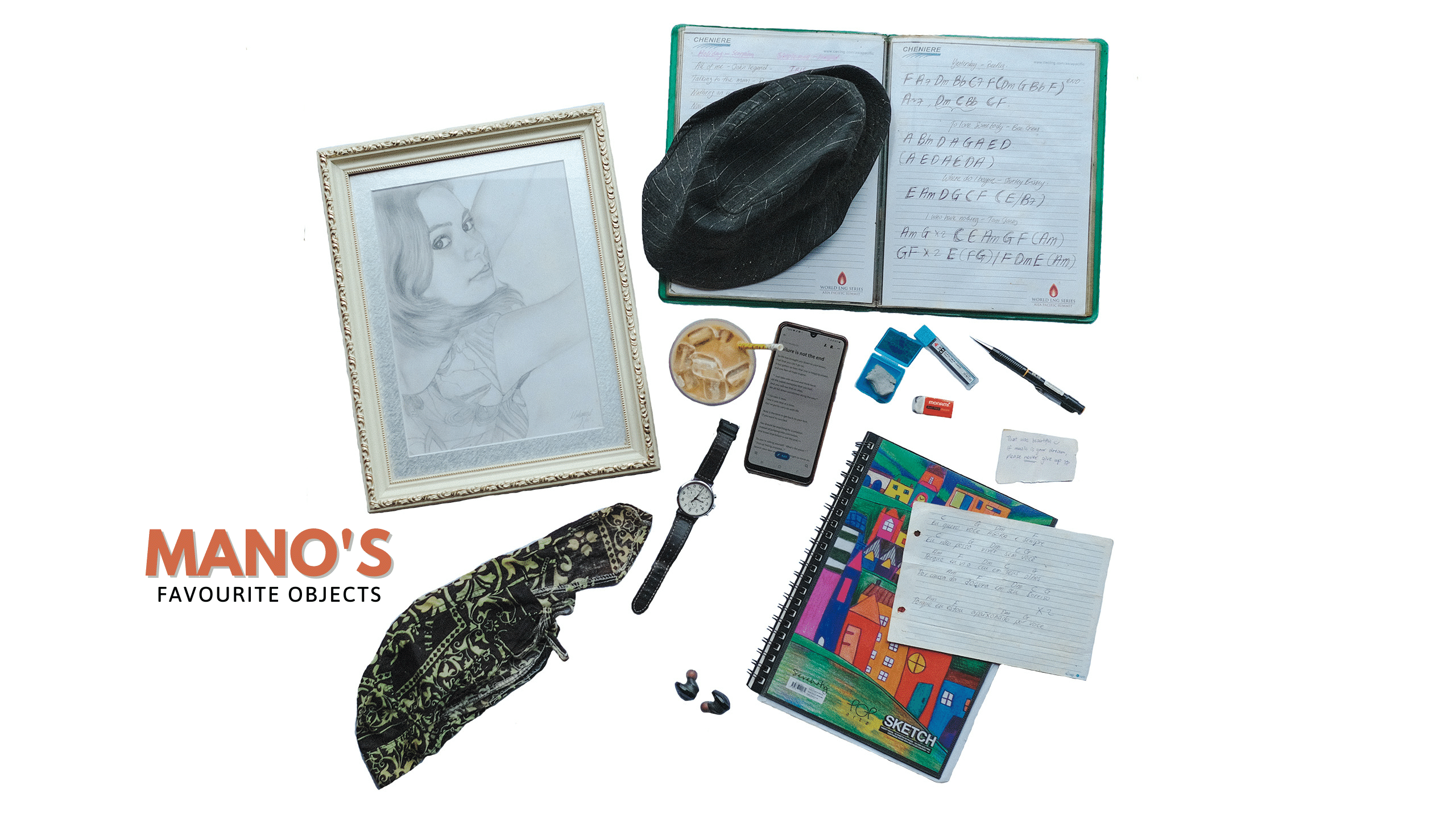

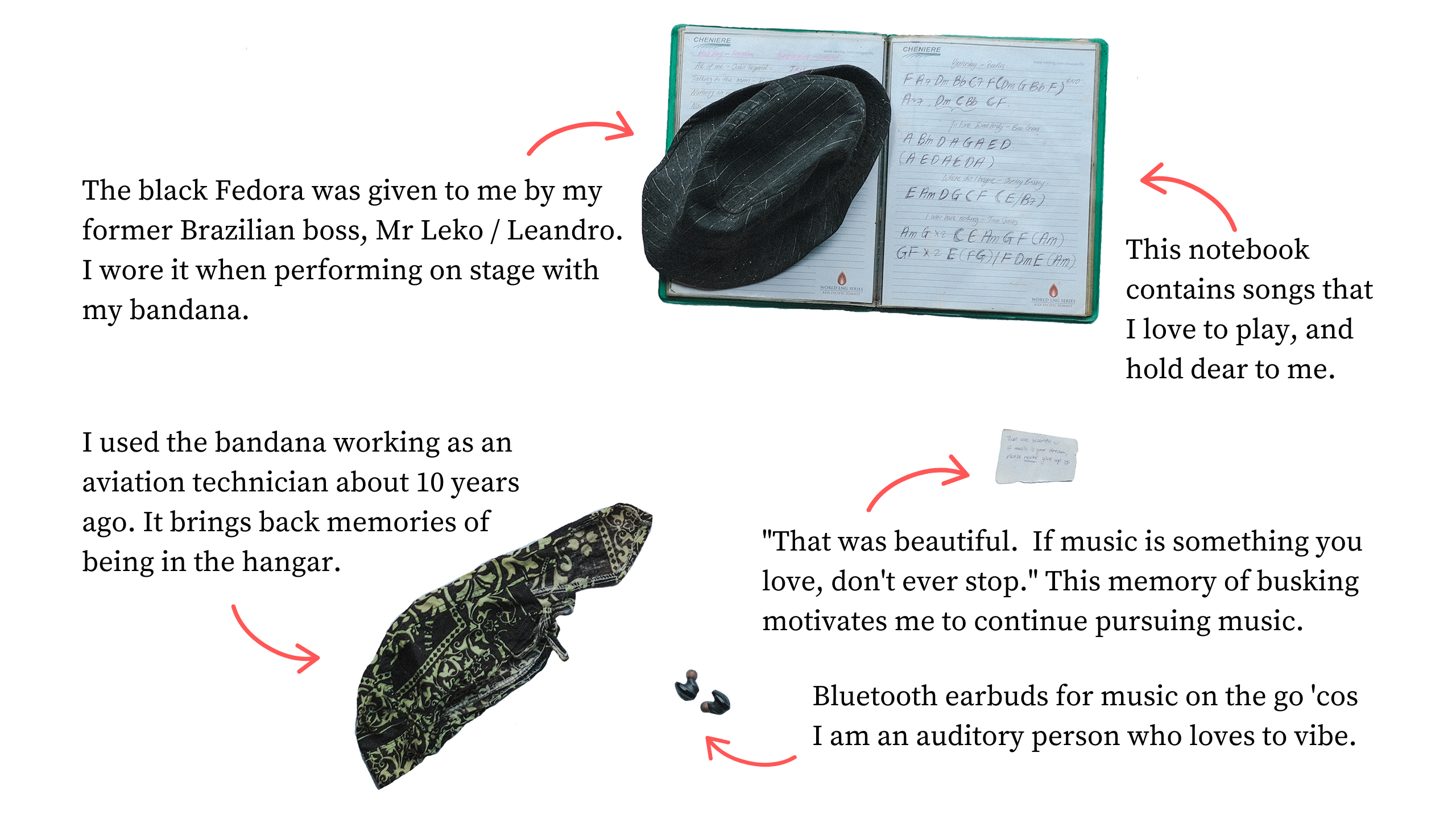

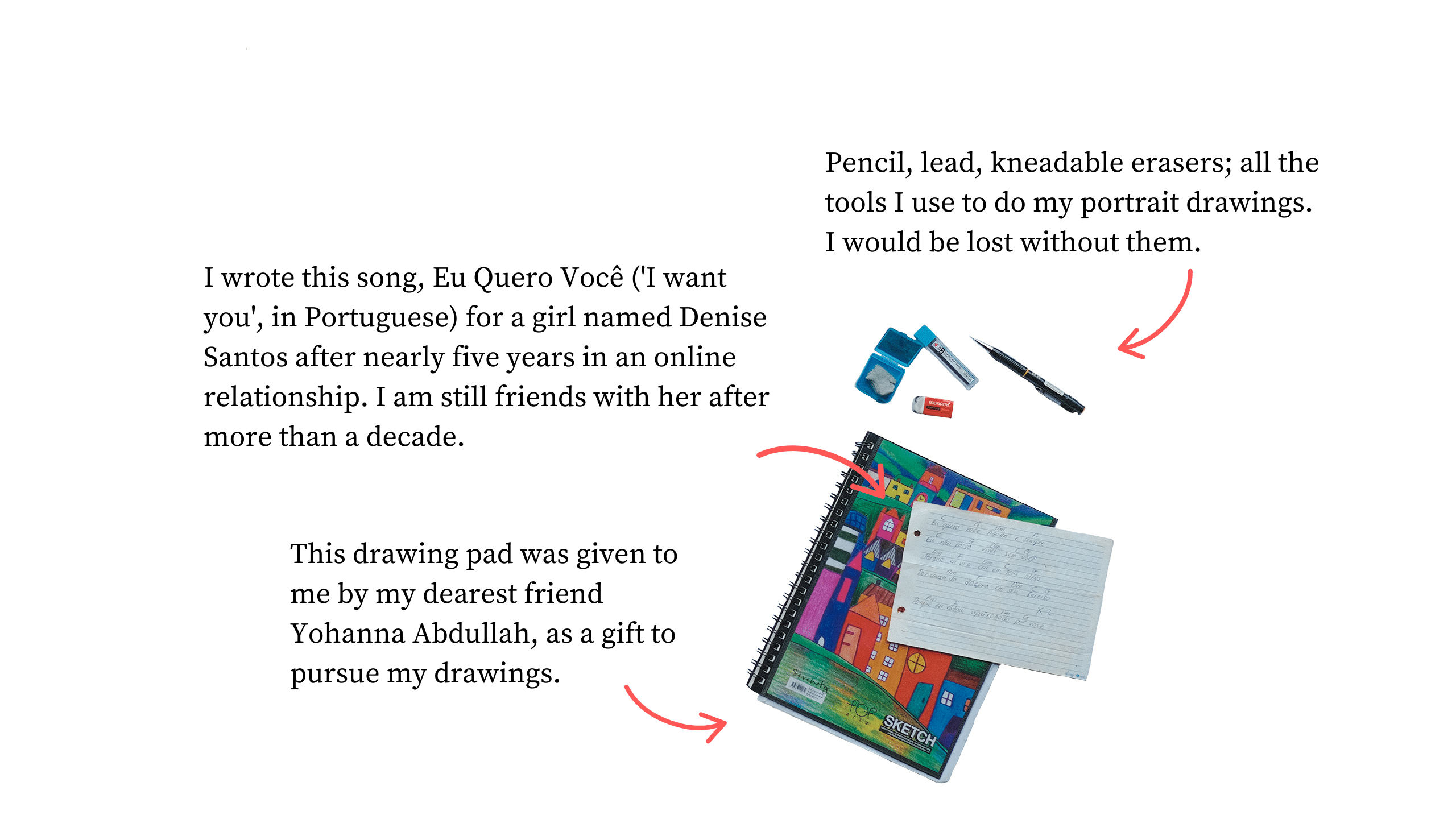

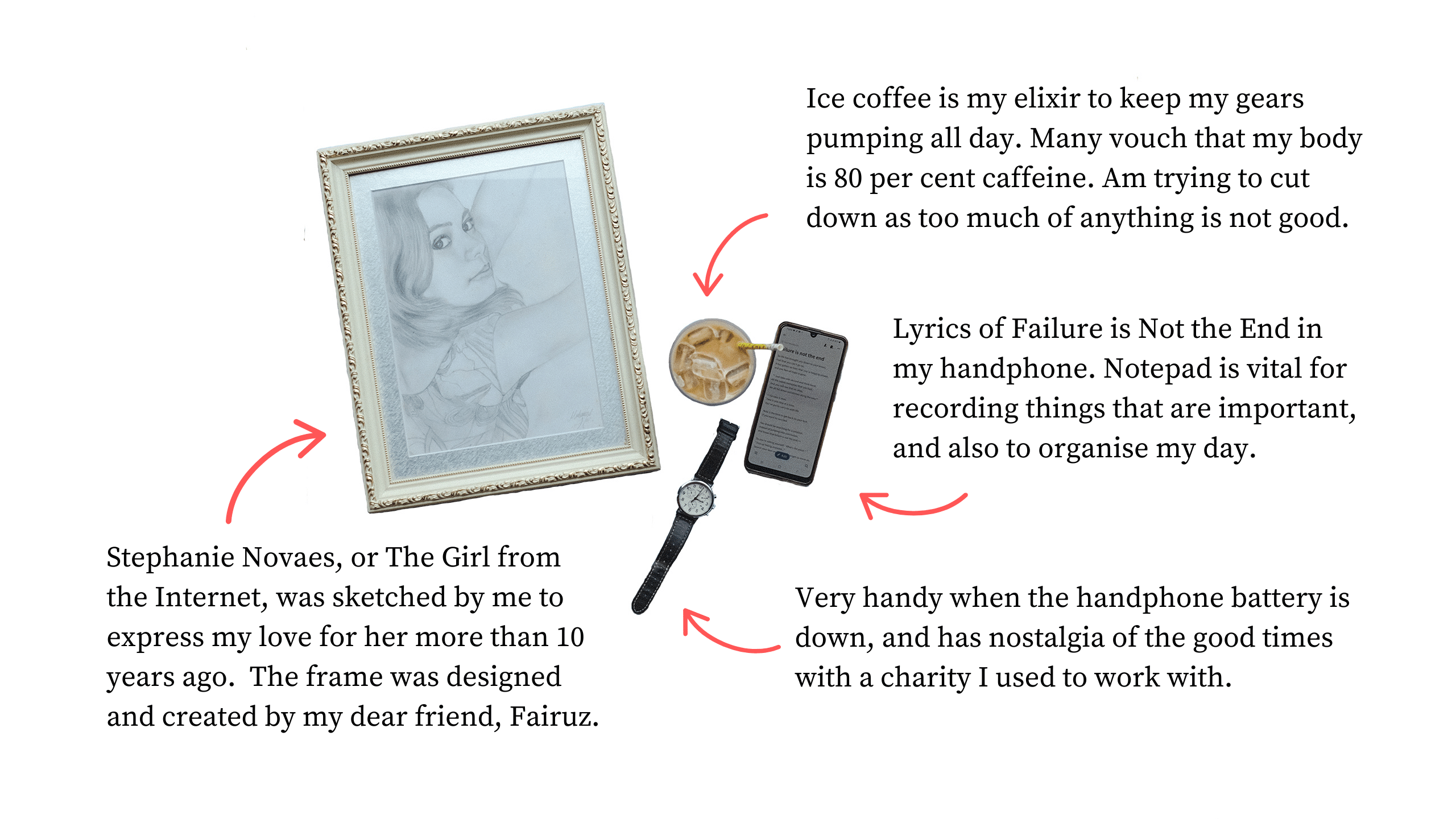

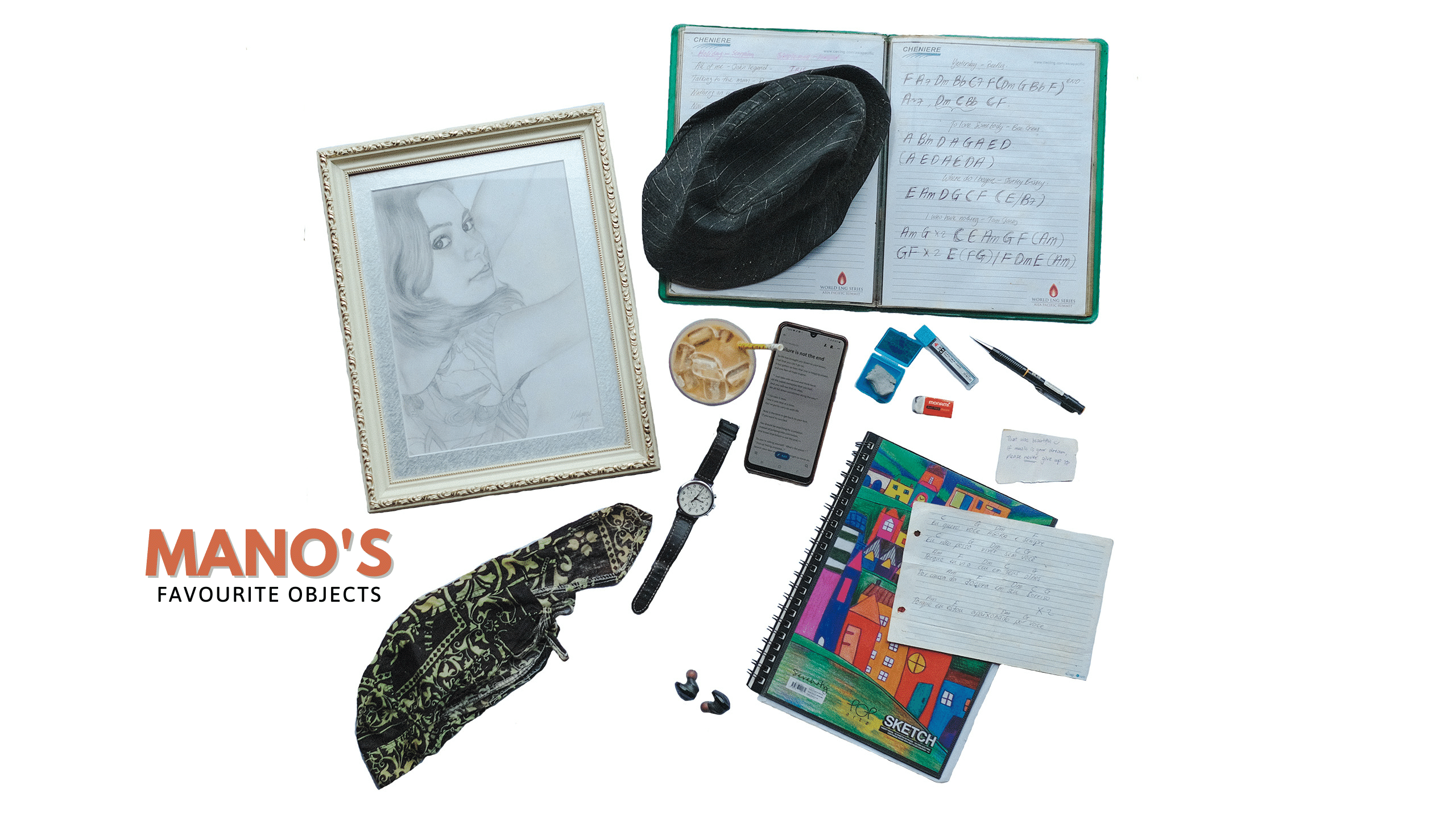

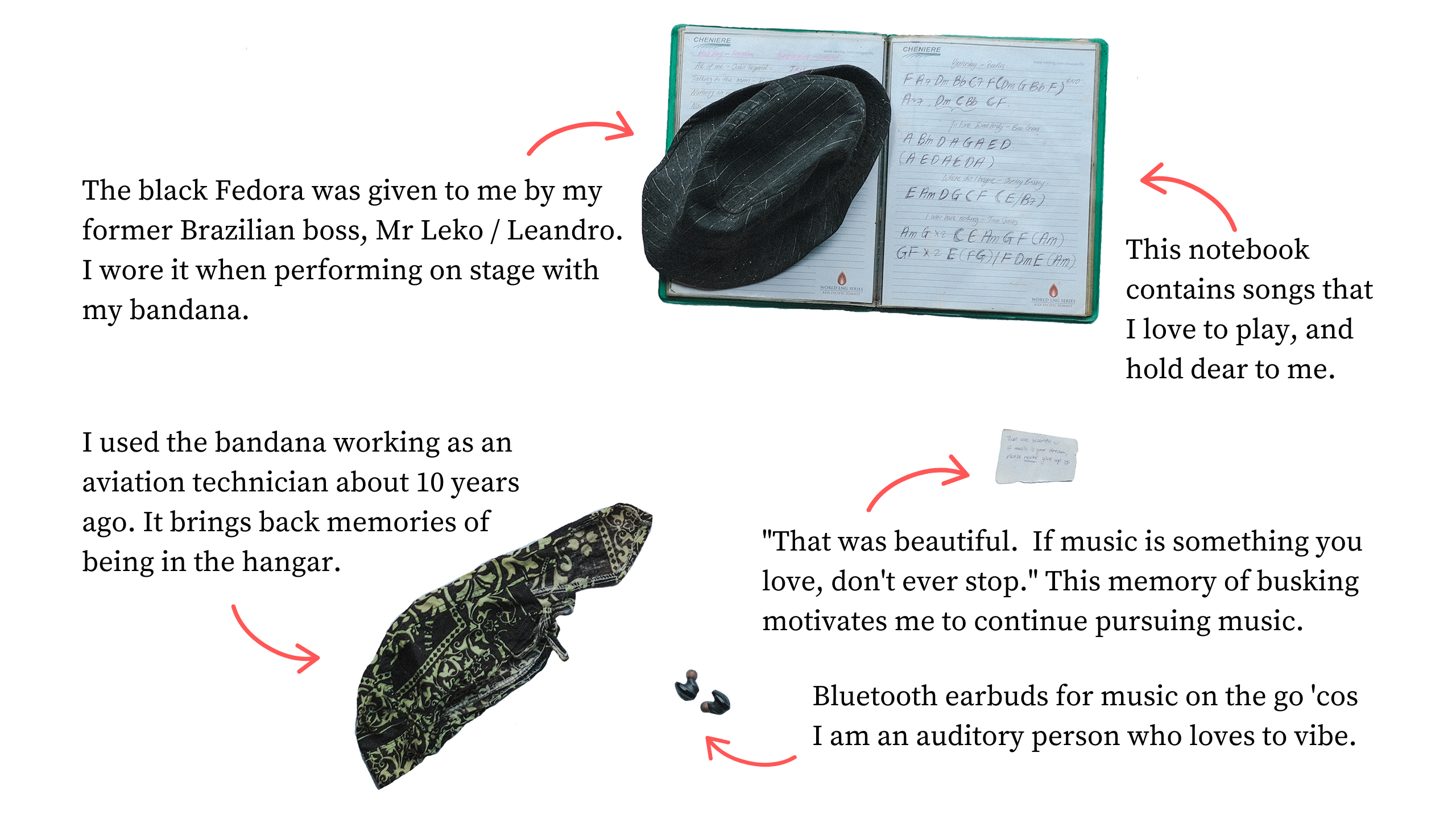

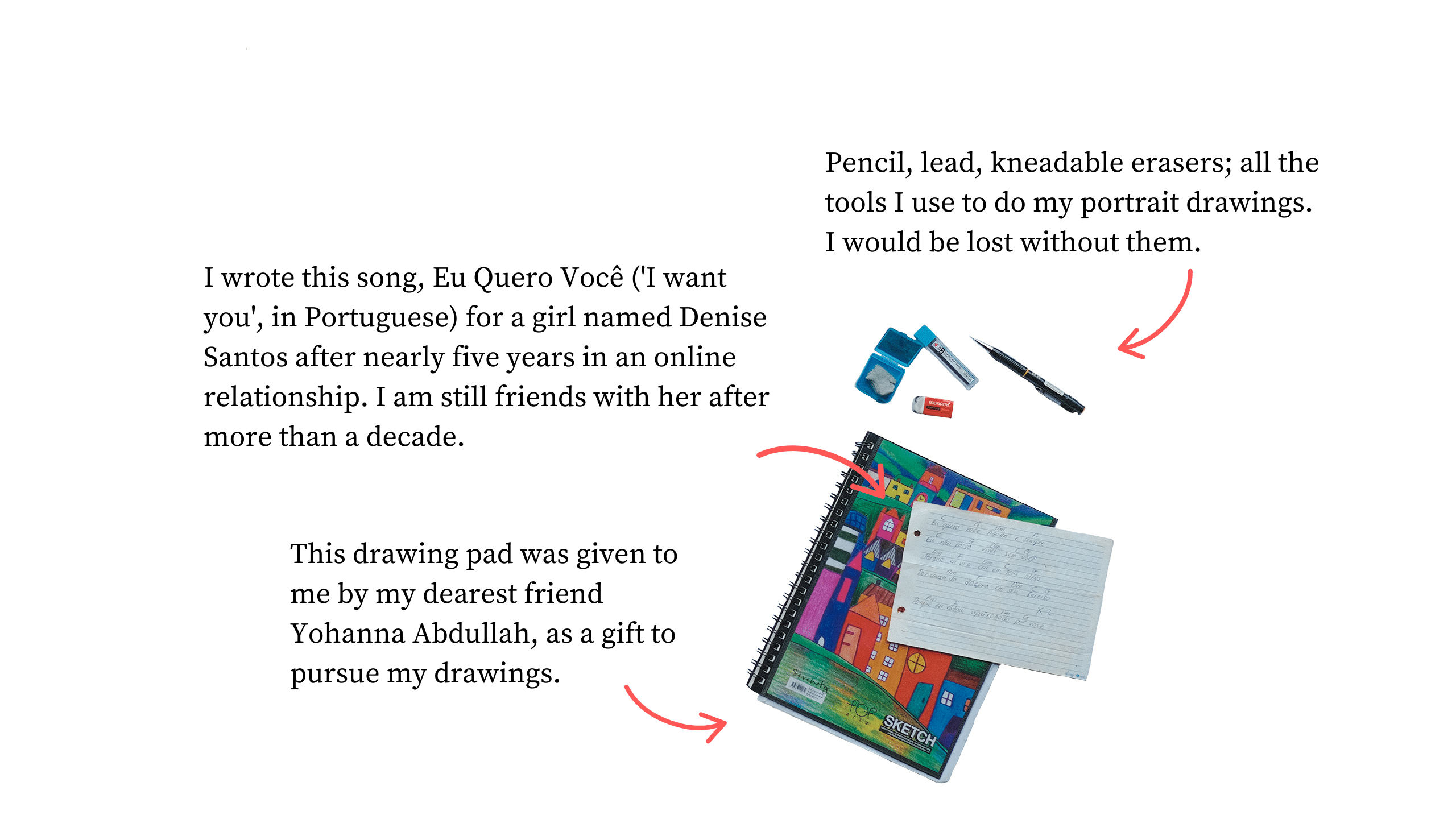

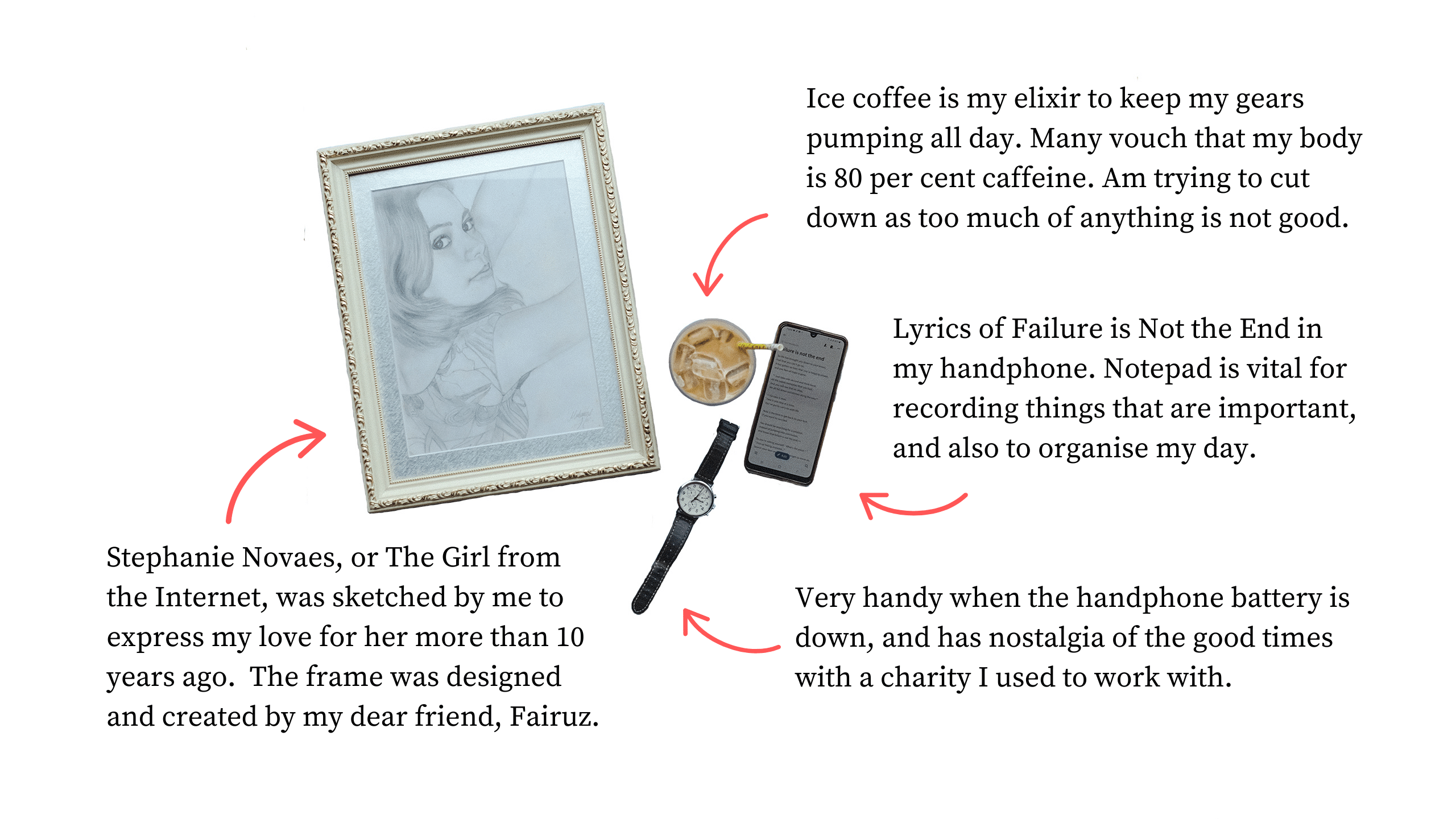

Mano Esperanza, 39, Musician and Busker

Mano Esperanza, 39, Musician and Busker

Jolyn, Mahita, Mano, Nicole and Shafiqah offer a glimpse into their lives growing up, and its impact on their adulthood.

“When I was younger, I was in a very competitive environment. I was being compared to my cousins or classmates… I cannot make a single mistake, everything needs to be perfect. This puts so much pressure on myself. It's very unhealthy. And all this stems from society and the environment we are in.”

“It was not an exceptional upbringing. Had a teacher who thought I was a no-hoper. But I just thought that was school. I was different.”

“My childhood wasn't that great… The tradition growing up in the 90s, how your parents discipline you. I had my uncle and my grandma, who took care of me. My mum and dad wasn't around. It taught me a lot about enduring life.”

“Since young, we, my sister and I weren't really taught self-love. We never really knew how to because my mum herself… doesn't really know how to love herself as well. We have very low self-esteem… And it took us many years to learn how to actually love ourselves.”

Read instead

“I was a very loved child when I was young. But [after] I had a younger sister and two younger brothers… It was a bit confusing for me, I didn't understand why the attention shifted and got divided… I had to take care of myself, and [I thought] my parents didn't want me.”

In Singapore, suicide is the leading cause of death for those aged 10-29 years. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, 452 lives were lost to suicide in 2020, the highest figure since 2012, and five times more deaths than transport accidents.

According to non-profit suicide prevention centre Samaritans of Singapore (SOS), the increase in suicide deaths was observed across all age groups.

“Mental health is worsening in society, given the anxiety and losses that people have had to face with COVID-19,” says Senior Clinical Psychologist, Dr Elaine Yeo from Promises Healthcare.

“Significant losses of certainty, safety, financial stability, personal boundaries and social connection; any of these stressors can lead to suicidal ideation and attempts,” explains Dr Yeo.

Senior Consultant from IMH Dr Jared Ng agrees that the pandemic has worsened the mental health of individuals, but warns against blaming everything on the pandemic.

“If you look at the suicide rates in Singapore over the last 10 to 20 years, we have hovered around 400 suicides a year. Next year’s numbers will be important for us [to gauge the reasons for the increase]." he says.

Not everyone who thinks about killing themselves acts upon it or ends up dying after an attempt. A recent study on suicidality by IMH found that one in 13 adults in Singapore had thought about suicide at some point in their lives.

According to experts, there are two broad types of suicidal ideation - active and passive. The former happens when a person becomes preoccupied with thinking about dying, and has started to form a plan. The latter occurs when the person wants to die, but these thoughts remain in the background, and can be fleeting.

“People have suicidal ideation because they are in intense emotional pain and in their helplessness and hopelessness, death and suicide feels like the only way to eliminate the pain.”

The tipping point that pushes someone to attempt suicide depends on how much stress a person can handle, says Dr Ng, and can vary according to age and sex, and is not always due to a mental condition.

“People have a misconception that only if you have a mental illness will you kill yourself. That’s not necessarily the case.”

Dr Ng explains, “Patients with mental illnesses are at higher risk, but we see many cases not diagnosed. They are undergoing so much stress in their life and that overwhelms their coping mechanism.”

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), suicides can “happen impulsively in moments of crisis.” These stressful events can include but are not limited to: separation and divorce, bullying and discrimination, losing a loved one, loss of employment, legal and financial problems, chronic pain and diagnosis of a terminal illness, like cancer.

Research also shows that a “disruptive or negligent household” can generate suicidal thoughts in children and teenagers.

Repeated and multiple experiences of abuse and trauma are also ripe for destroying a person's ability to regulate their emotions, tolerate distress, engage in problem-solving and self-soothe, says Dr Yeo.

“A person who has experienced trauma is more likely to feel that they cannot cope in the face of distress, therefore viewing suicide as the only option and increasing their risk of developing suicidal ideation.”

Dr Yeo says that people with suicidal ideation believe that they have tried every possible avenue to get rid of this pain, but have failed.

Also called ‘cognitive contraction’, people who have lost all hope experience tunnel vision, or as Senior Consultant Psychiatrist Dr Jacob Rajesh of Promises Healthcare explains, “black and white thinking, seeing things as all or nothing, good or bad.”

“They start to consider the means by which they can kill themselves and abandon their reasons for living and their future dreams.”

Standing on the edge

Suicidal ideation often never goes away, and suicide attempt survivors are said to be at a greater risk of suicide than the rest of the population. But nine out of 10 people who attempt suicide and survive “will not go on to die by suicide at a later date.”

Many who have survived suicide attempts but still live with suicidal ideation have learnt to understand and embrace it, thus tempering its effects. This has enabled them to continue to live fulfilling lives.

WATCH: Mahita explains what it is like to live with suicidal ideation.

Being mindful of the precarity of life and the fragility of one’s mental well-being has become a survival mechanism strengthened over time.

Notes Mahita, “Since my very first suicide attempt, I've learned to be in tune with how I'm feeling with what's going on in my head.” But the fear of succumbing to the ideation “scares” her, and Mahita believes it “will never go away”. “It's also that very same fear that keeps my awareness level high,” she adds.

A significant part of dealing with the lingering thoughts of killing herself has been about sticking to a strict regimen of medication for bipolar disorder, which helped her manic highs and depressive lows.

If she is feeling suicidal, and even standing at the balcony becomes a potential hazard, she tells her husband and they pay an emergency visit to her psychiatrist.

The added toll comes with having to erect a facade.

“When there's family or friends I can't let them know. I don't want to burden and alarm them... I have to pretend that everything's alright.”

Mano's earlier busking days. (Photo courtesy of Mano Esperanza)

Mano's earlier busking days. (Photo courtesy of Mano Esperanza)

Others have learnt to be aware of their cycles of emotional highs and, particularly, lows.

Mano says his mood tends to dip towards the end of the year and during this time, he is “very suicidal”. To counter this deep impulse requires him to “psycho” himself into feeling better.

“How I managed to dig myself out of the hole was that I tried to evaluate, 'am I expecting too much from life? What's the best I can do about this situation?’” he explains.

“Things are not fantastic...but being alive is still being alive.”

In February 2021, Shafiqah found herself in the hospital after trying to take her life again, which put her in a coma for eight days. She says that her loved ones thought she “wasn’t going to wake up.”

Returning from the brink of death is often a bittersweet moment: “When we wake up, we may feel really disappointed,” points out Shafiqah, adding that one is also faced with a barrage of questions and insensitive remarks.

“The minute we wake up, they will be asking, ‘Why do you want to end your life? Don't lah, don't need to. You have everything you want in your life’” she elaborates. “That makes...all of my pain so futile.”

It was also while she was in the psychiatric ward that she discovered many others her age who shared the same thought patterns and experiences.

“When I heard some of their stories, some were really heart-wrenching, but they still wanted to live because they wanted to experience life. That opened my eyes to more possibilities [of living].”

Photo courtesy of Mano Esperanza

Photo courtesy of Mano Esperanza

Find out what situations cause distress to Shafiqah and Jolyn, and how they anticipate, recognise and manage them.

Before you do, remember to take a breather. Here’s a list of hotlines in your region, if you need them.

Read instead

“I can get very impulsive when I'm stressed and do extreme things. So I try and minimise my stress. When I do have these kind of emotions, or feel like they're gonna come, I don't push them down or ignore them. Instead, I feel them and let them go. These are things I've learned thanks to therapy and friends.”

Read instead

“When there's a dip in sales, I feel very stressed. And I mean, very, very, very stressed. Because this is my only income. But I have to do it and there's no one helping me.”

A new life, new business and new relationships; mix in a competitive and perfectionist nature, which has been hardwired to succeed, and you have the perfect pressure cooker recipe for building up stress.

And the lid did blow off for Jolyn, whose first suicide attempt brought her teeteringly close to ending her life. But the thoughts of suicide have not faded.

“When it happens you can't think straight, there's no logic,” she says.

Understanding the way her mind works and learning how to tame it has been instrumental in the way she deals with her “tangled mind”, where the self-critical voice feeds a constant stream of internal conversations.

“The angel is telling you, 'You are the best. You know what you're capable of. You can do this, you are enough. You know you're enough,” describes Jolyn.

But on the other side is the “devil” saying, “‘No, let yourself feel emotions, you're already really very depressed, just go down the spiral.’ It's a huge struggle between letting yourself feel the emotions and just go downward. Or stopping yourself, and bringing yourself out of that situation.”

She has eschewed seeking therapy, due to her simmering distrust of “so-called professionals” after her experience with a school counsellor, who shared what she said in confidence with other teachers.

“He was so critical and judgmental. And he broke his promise. I was an 18-year-old girl who placed her trust in the teachers and school counsellor thinking her little secret is safe, but it's not.”

Nicole shares a similar experience with a therapist after surviving her suicide attempt.

“He was asking me the same questions... which made me feel like there's no progress,” she says, but continued to take the medication he had prescribed her, which only made things worse.

“I became anorexic, I couldn't eat. I was vomiting everything, even liquid. I was still going through hell with that stalker. And the therapy doesn't help and I'm barely sleeping.”

Nicole’s life continued to spiral out of her control, until she decided to drop everything and travel by herself.

“I travelled to a lot of countries; getting my mind cleared and trying to find myself again. When I came back... I forced myself to get a job. And that's where I met my husband. He helped me a lot and pulled me out of my dark thoughts.”

Coping with ideation

Developing a set of coping mechanisms can make all the difference. And there are no limits as to what works to soothe, silence or distract from those suicidal thoughts.

WATCH: Mano takes us down music memory lane.

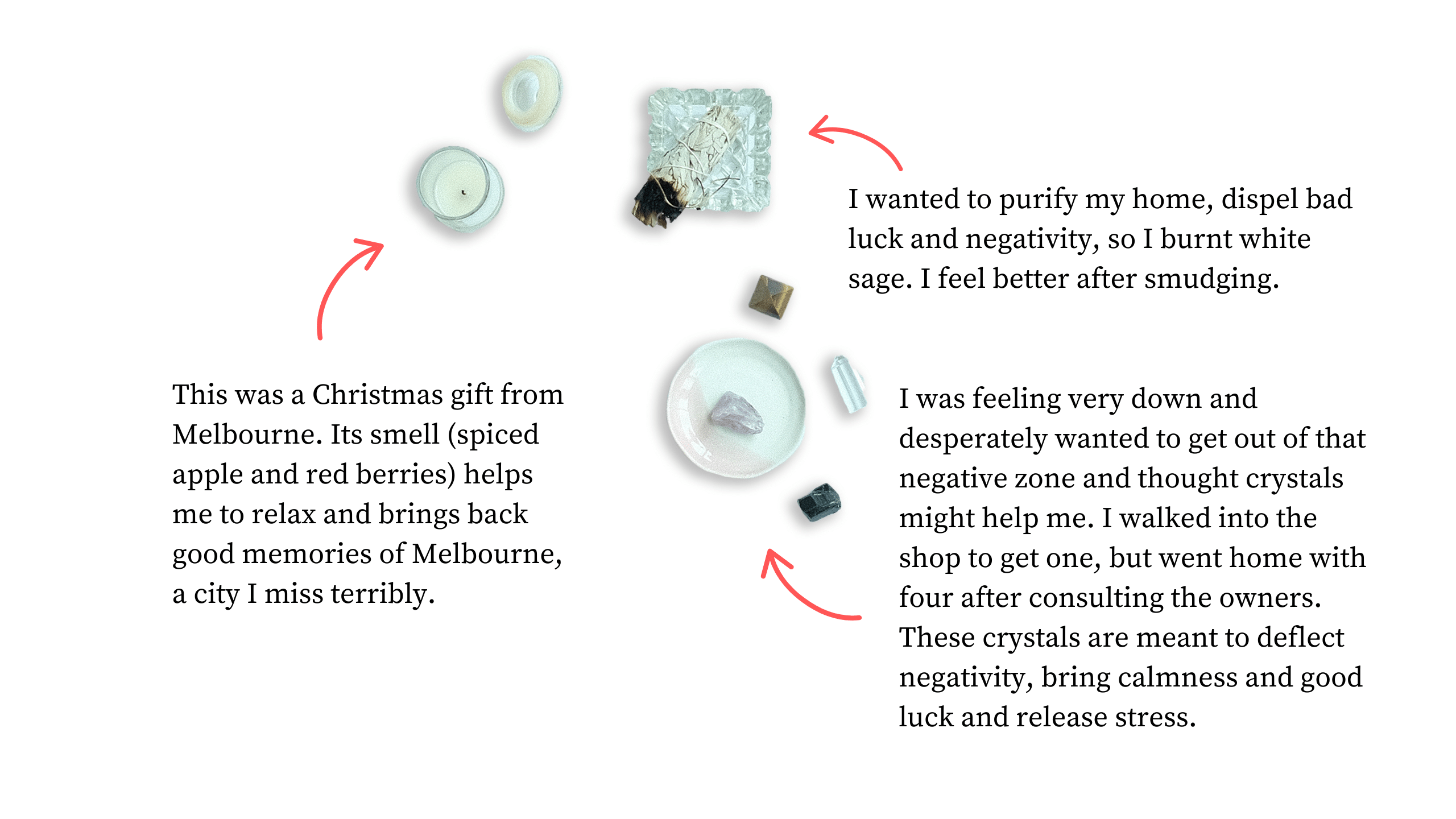

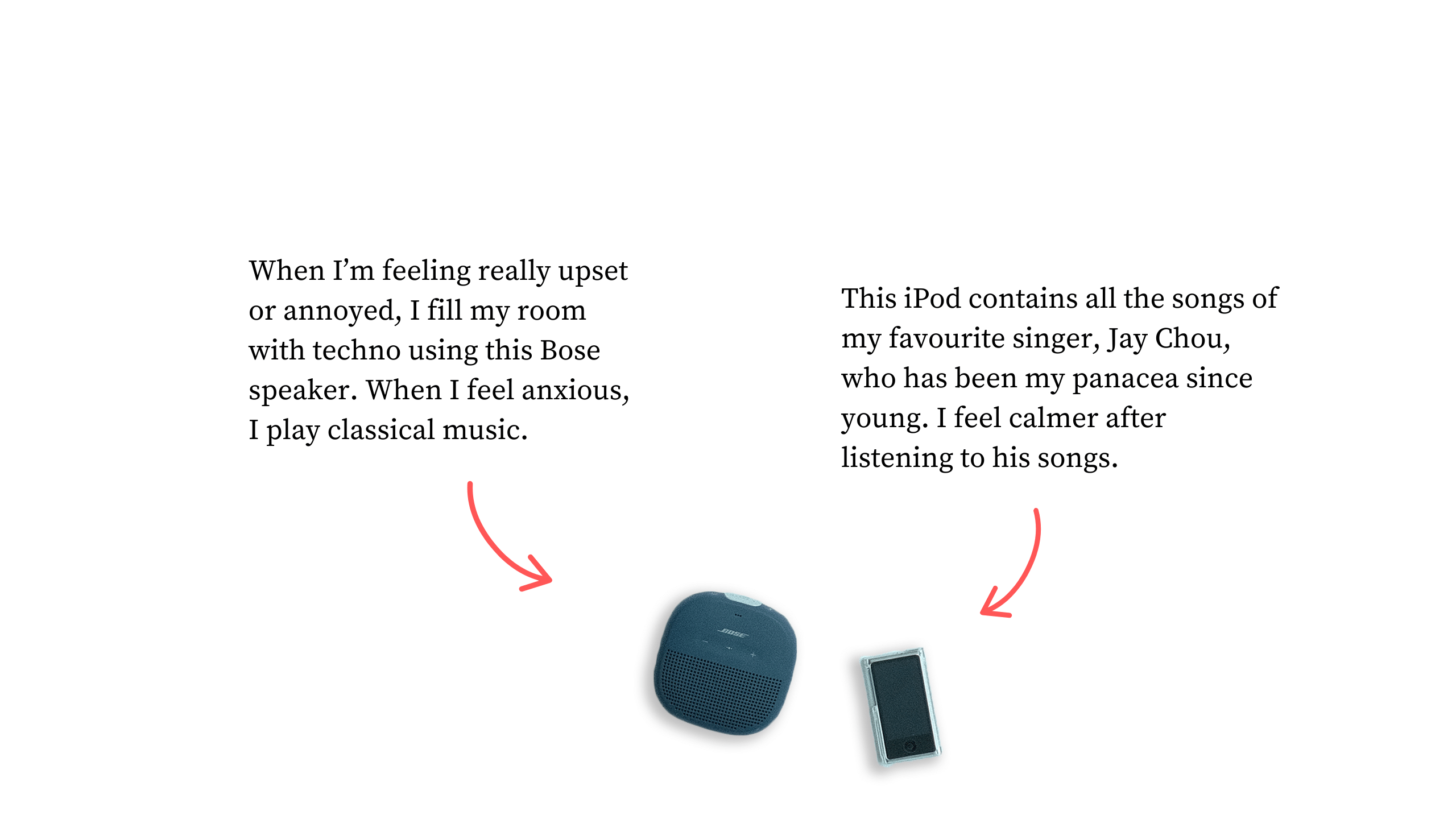

Besides the option to medicate, Mano, Shafiqah, Nicole, Mahita and Jolyn share their ways of coping.

At the end of this story, you can write a letter to your future self. If you’d like to go there now, click here.

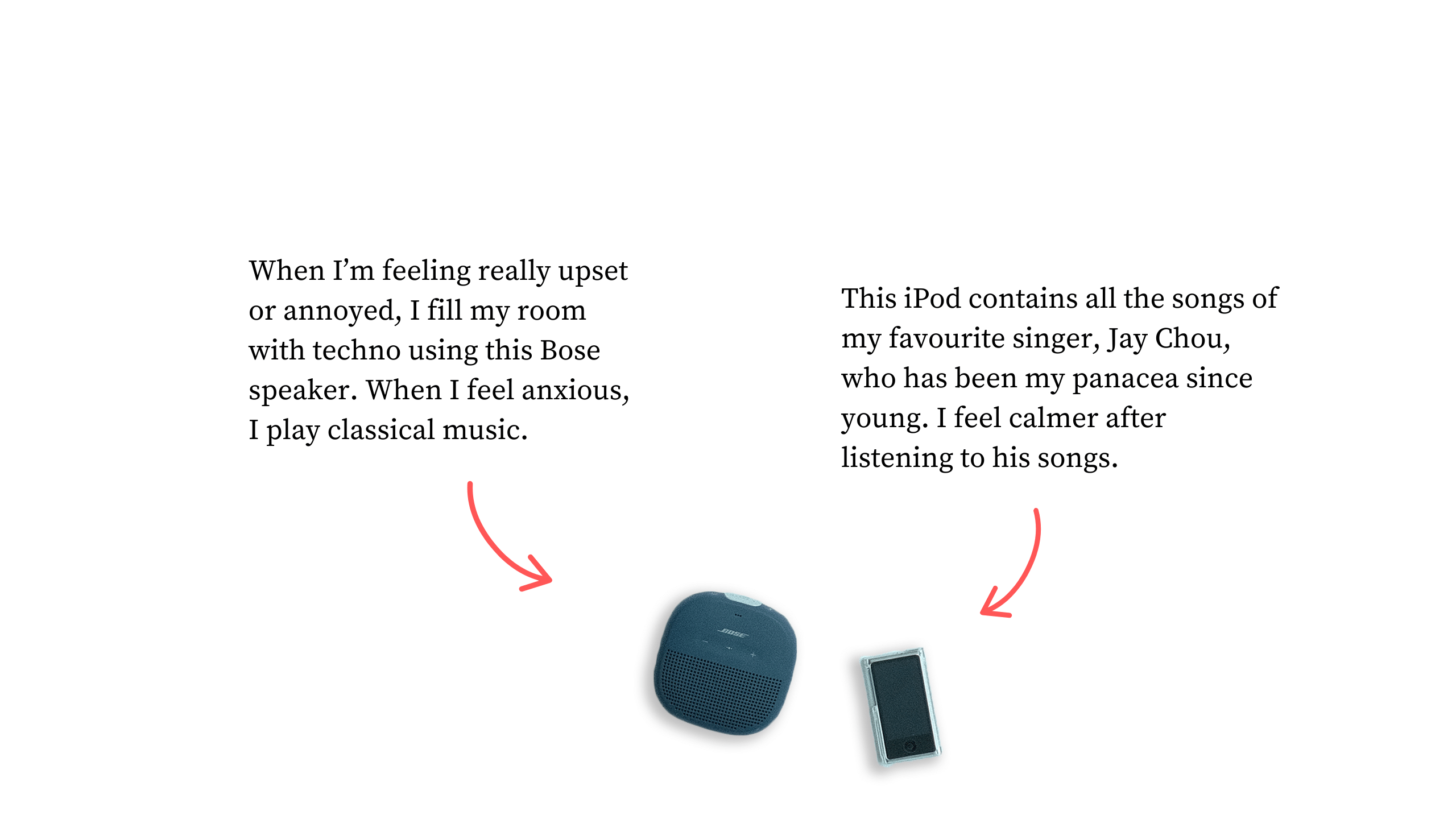

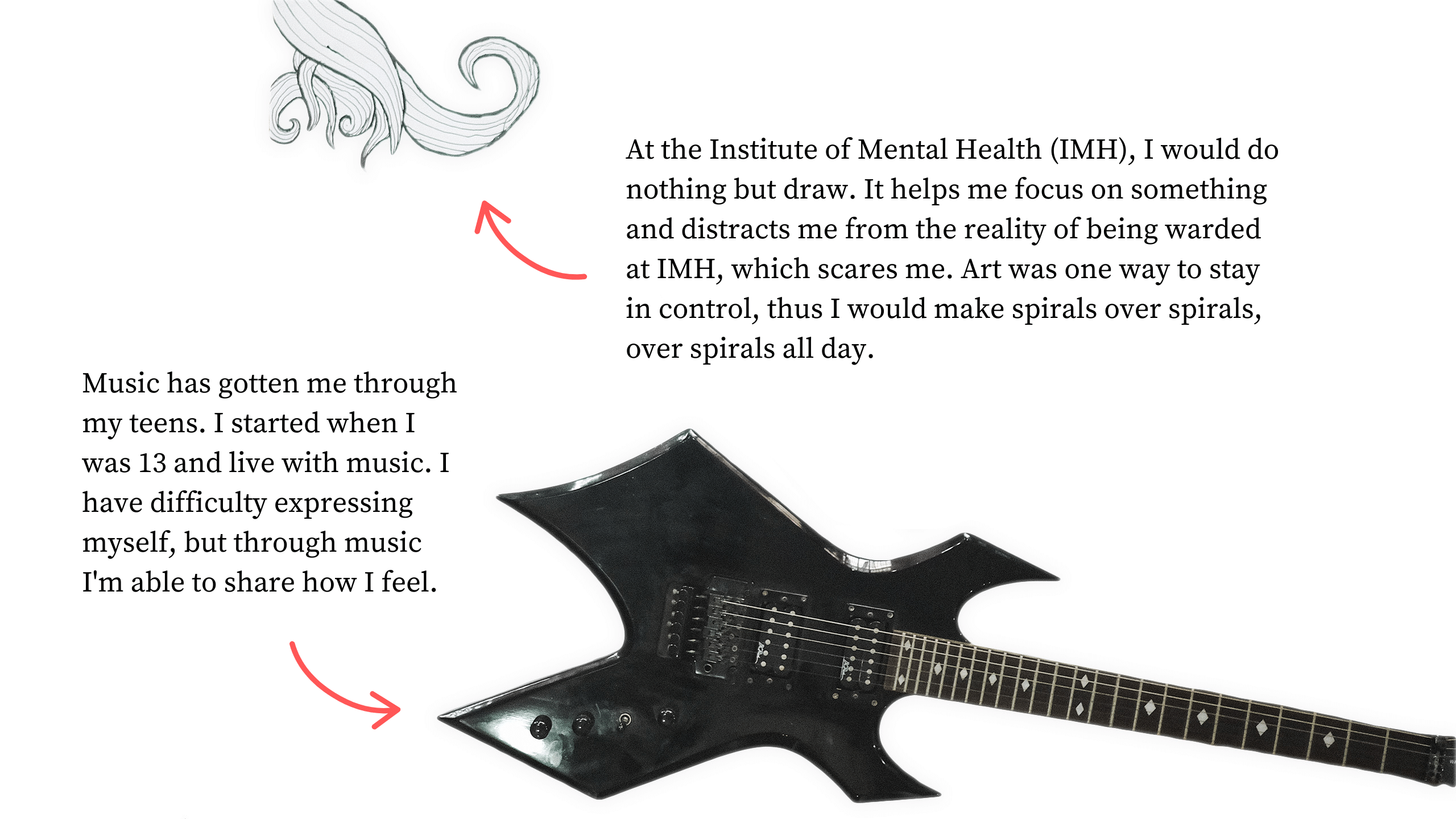

Whenever he feels overwhelmed, Mano turns to a few close friends whom he anchors himself to provide a safe and supportive space.

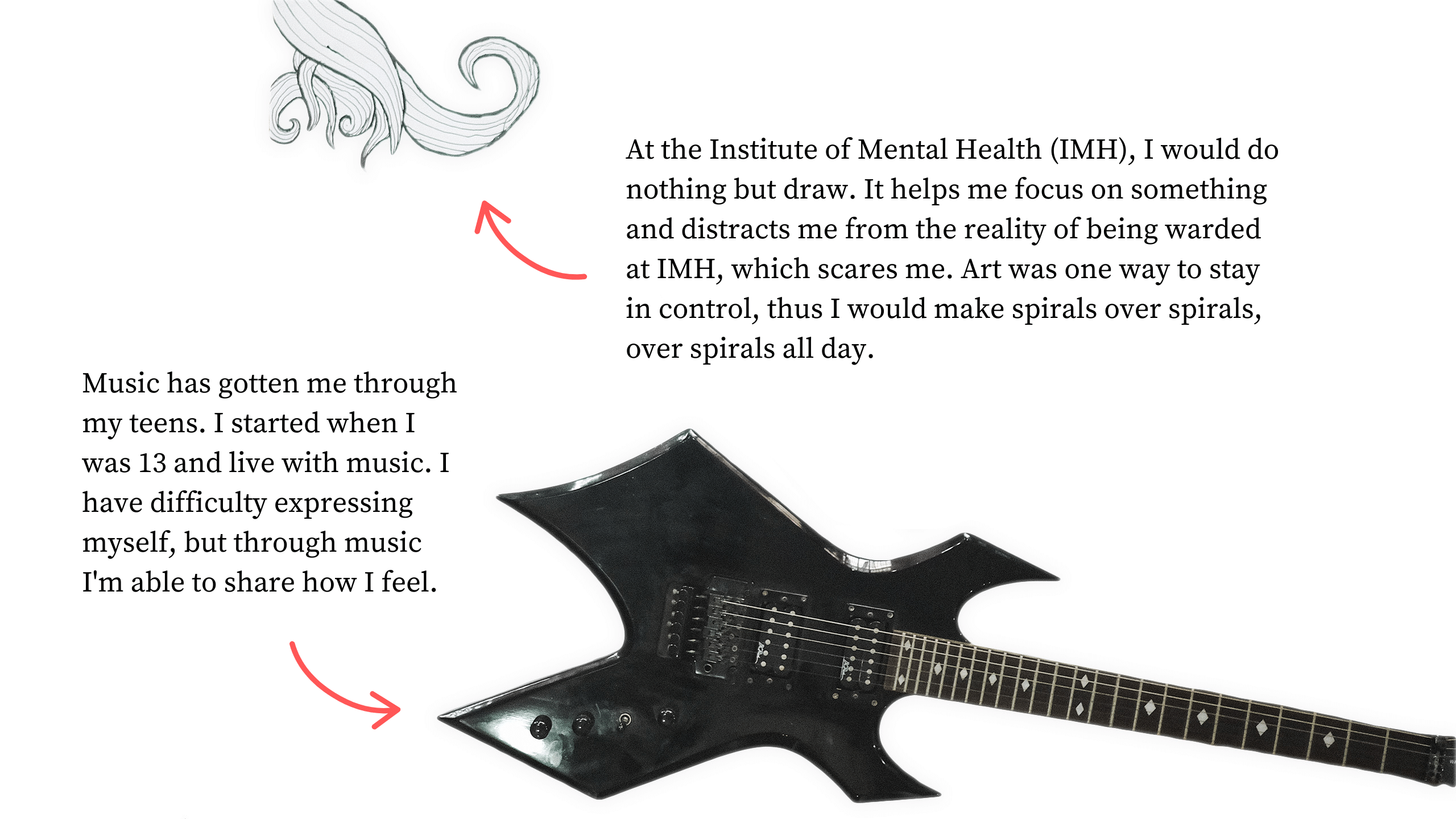

His guitar was also an anchor for “the longest time”, and whenever he felt down, he would “play the guitar and feel alive again.”

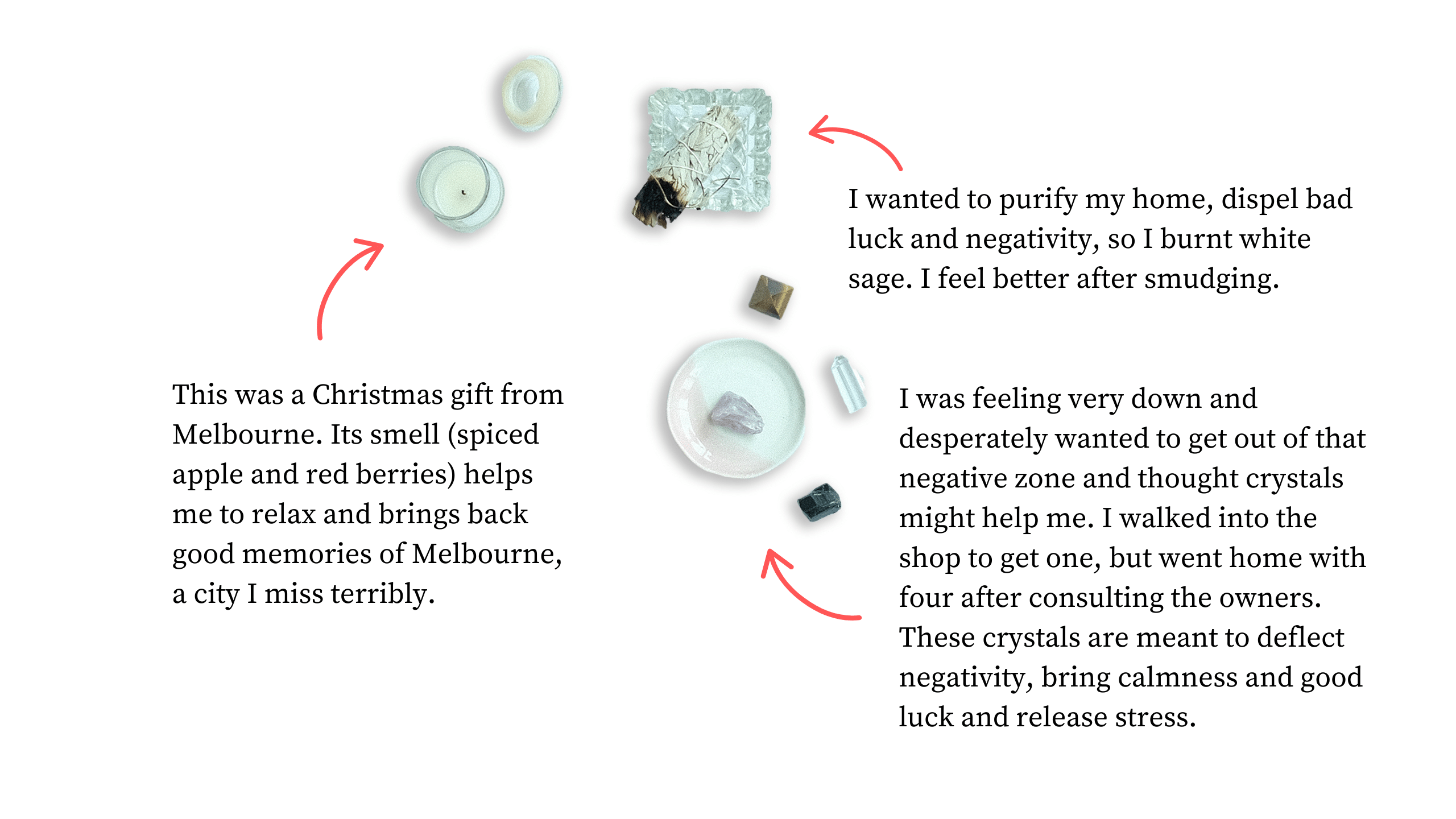

Drawing is a way for Shafiqah to channel her energy, when she is feeling triggered.

“In IMH, I would do nothing but draw. It helps me focus on something and distracts me from reality; being warded truly scares me. Art was one way I could still [be in] control. I would make spirals over spirals all day.”

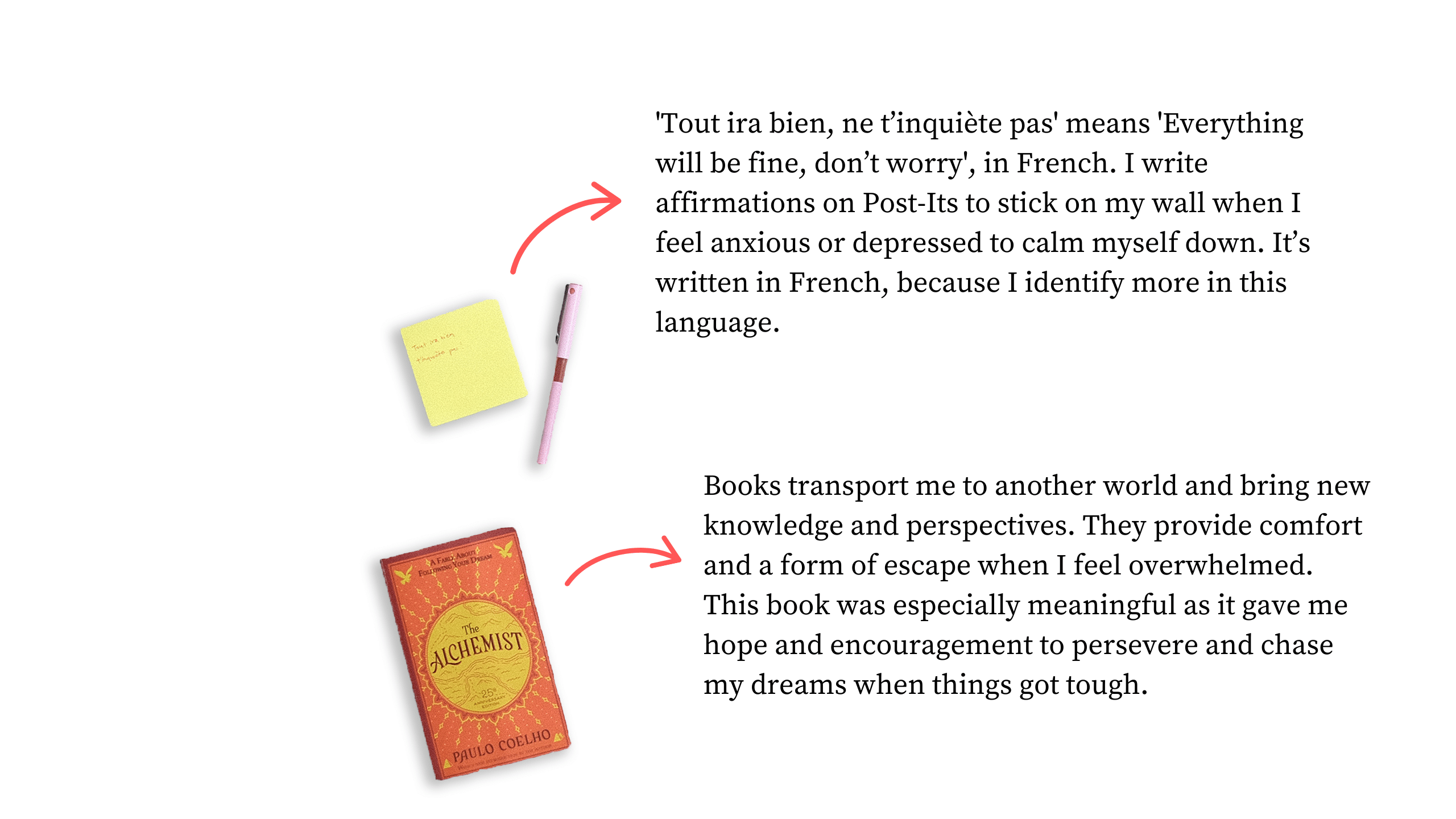

Jolyn also believes in the power of the written word.

The act of journaling performs a cathartic function, as it enables her to record and express painful and uncomfortable emotions.

WATCH: Jolyn reads the journal entry she wrote the morning after her first suicide attempt.

Bottle up one’s emotions for too long and you run the risk of exploding: “It’s much easier to push it down and ignore it. But at one point it's going to explode,” says Shafiqah, adding that she learnt it the hard way.

“When I feel really down and suicidal, I let myself cry and feel [the emotions]. At least I will be feeling in that moment, and would be able to let it go. If not, it would be piling over and over until a point where I cannot take it.”

Communicating with friends and loved ones is what Nicole and Jolyn turn to in times of need and distress. Even if it means being on the receiving end of criticism.

“Sometimes their harsh words remind me that things cannot always go my way. And sometimes my way is not the best way. I [also] distract myself every day with work, friends and family.”

“I found comfort in some of my friends,” says Jolyn. “At first I didn't want to tell them about [my] suicide attempt, but I needed to open up… I told people whom I trust that will not judge me, and will be there for me when I need them.”

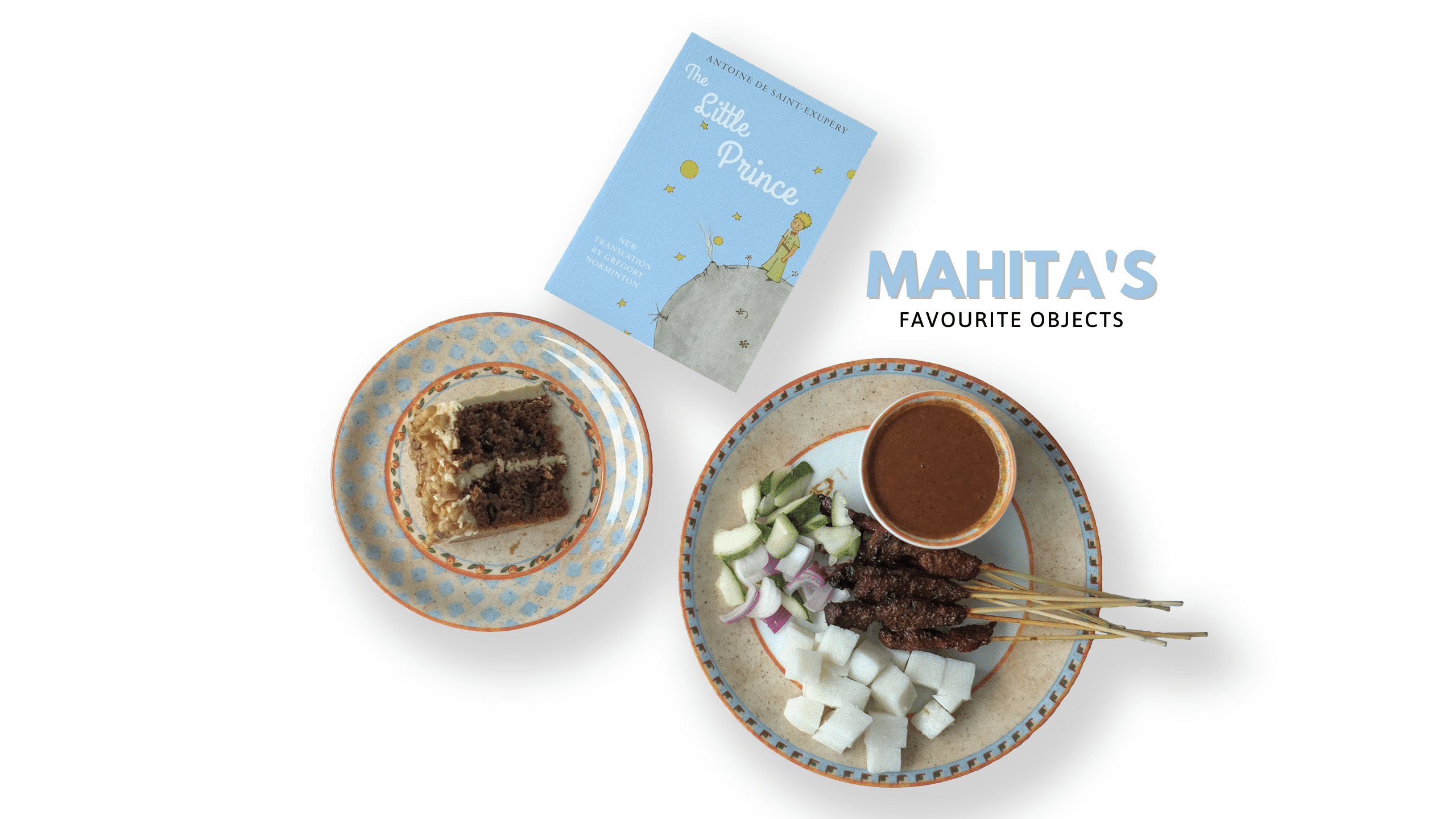

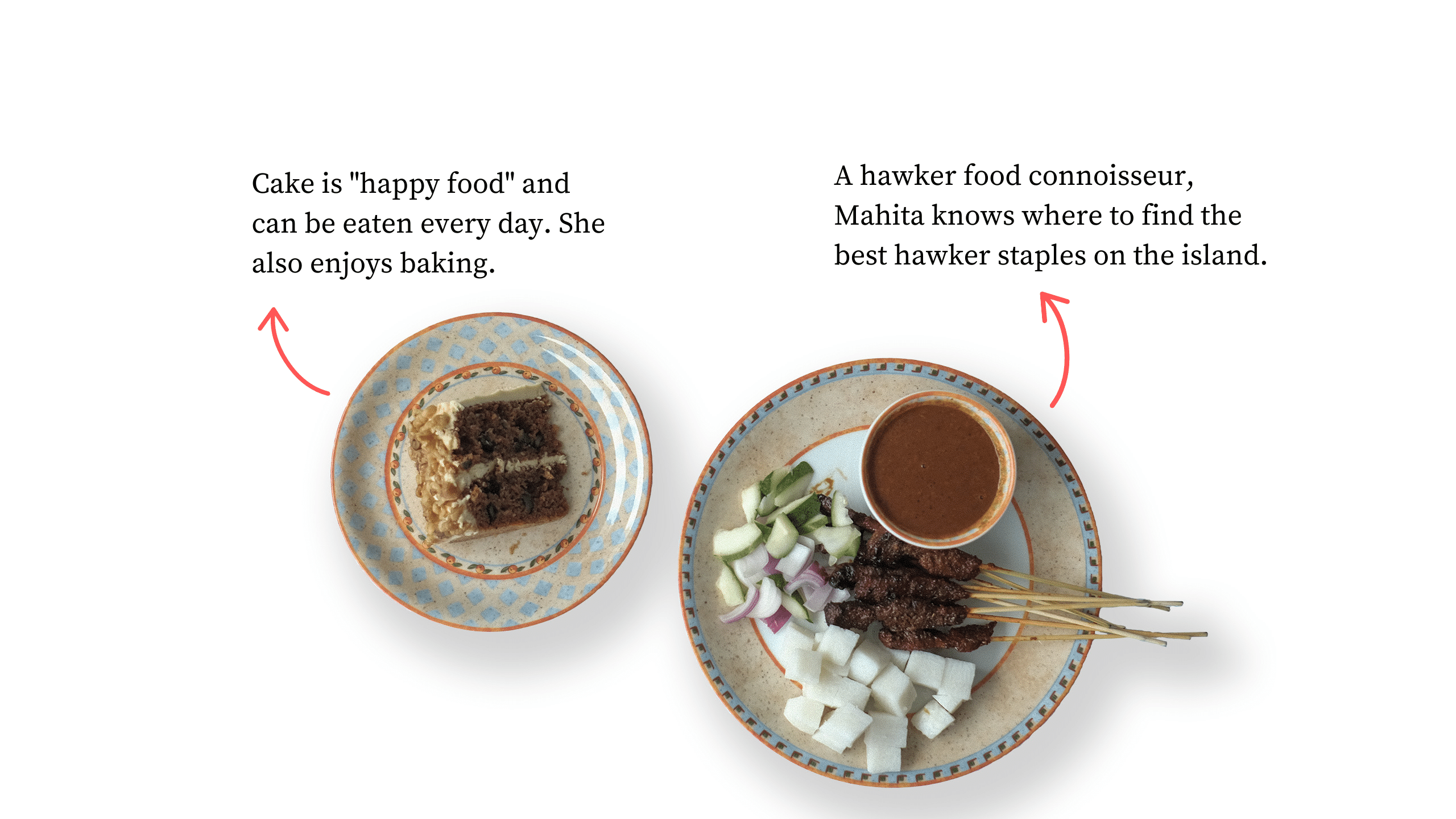

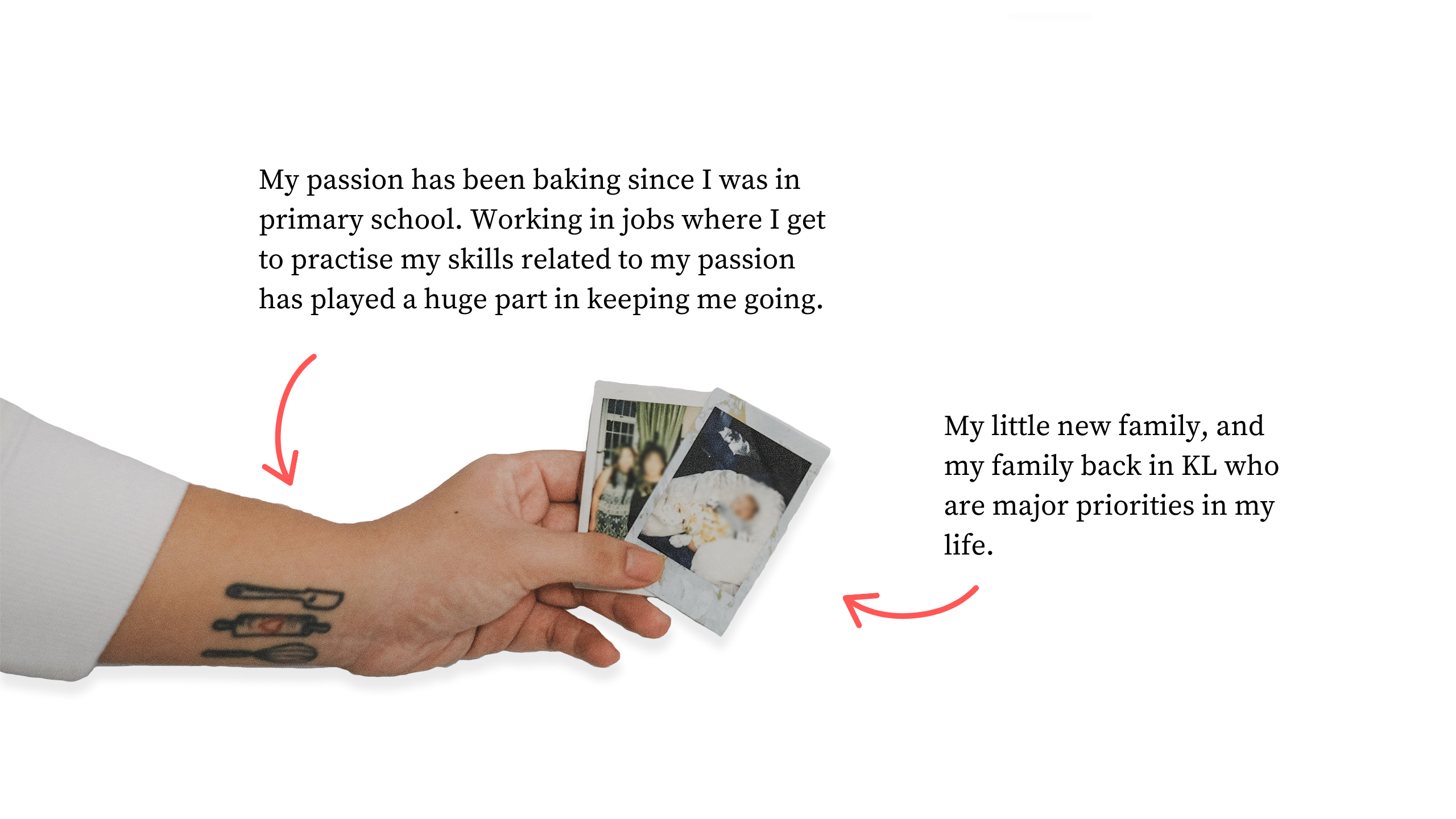

For Mahita, cake is her “happy food”, and she can eat it almost every day, if she feels down. Sometimes she bakes loaves and shortbread, while other times, she buys whole cakes, slices them up and sticks them in the freezer for a rainy day.

“Cake always makes me happy and then suddenly, I'm not suicidal anymore. After years of dealing and battling it, this is what I know works for me.”

Rest is essential and critical for Mahita - nothing less than eight hours, but she functions best on 10 hours of deep, uninterrupted sleep.

“If I get less than that, I can feel my whole mood drop,” she explains.

“It's not that I'm tired or sleepy, I just become different. I react in a way that I can be suicidal because of that.”

If talking, listening to music and journaling do not work at a particular moment, Jolyn resorts to throwing small items, like a key, onto the floor.

She explains why: “This is how I'm feeling, it's not a great thing and I'm throwing [it] aside. [Do it] a few times and [it] makes me feel better.”

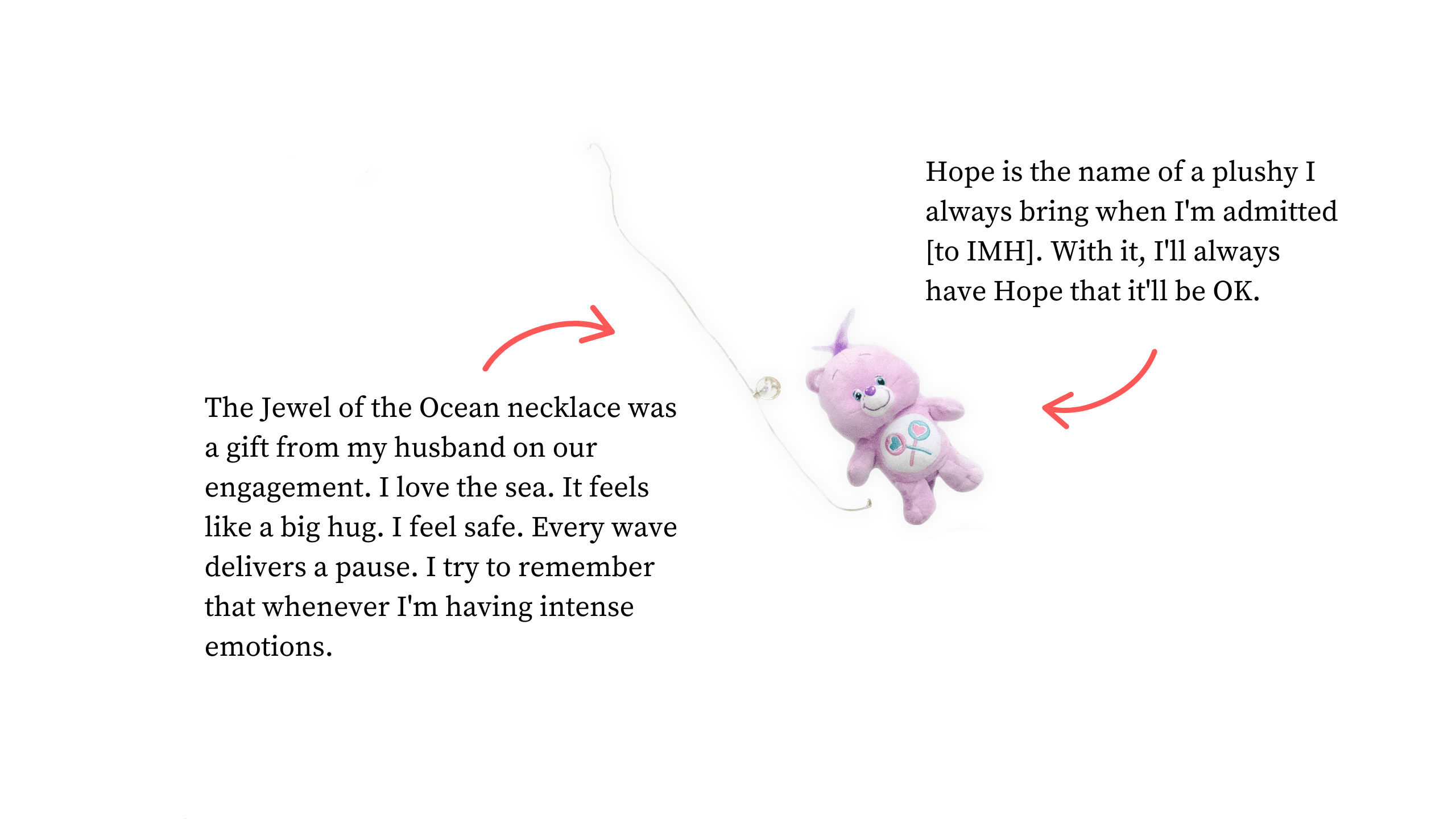

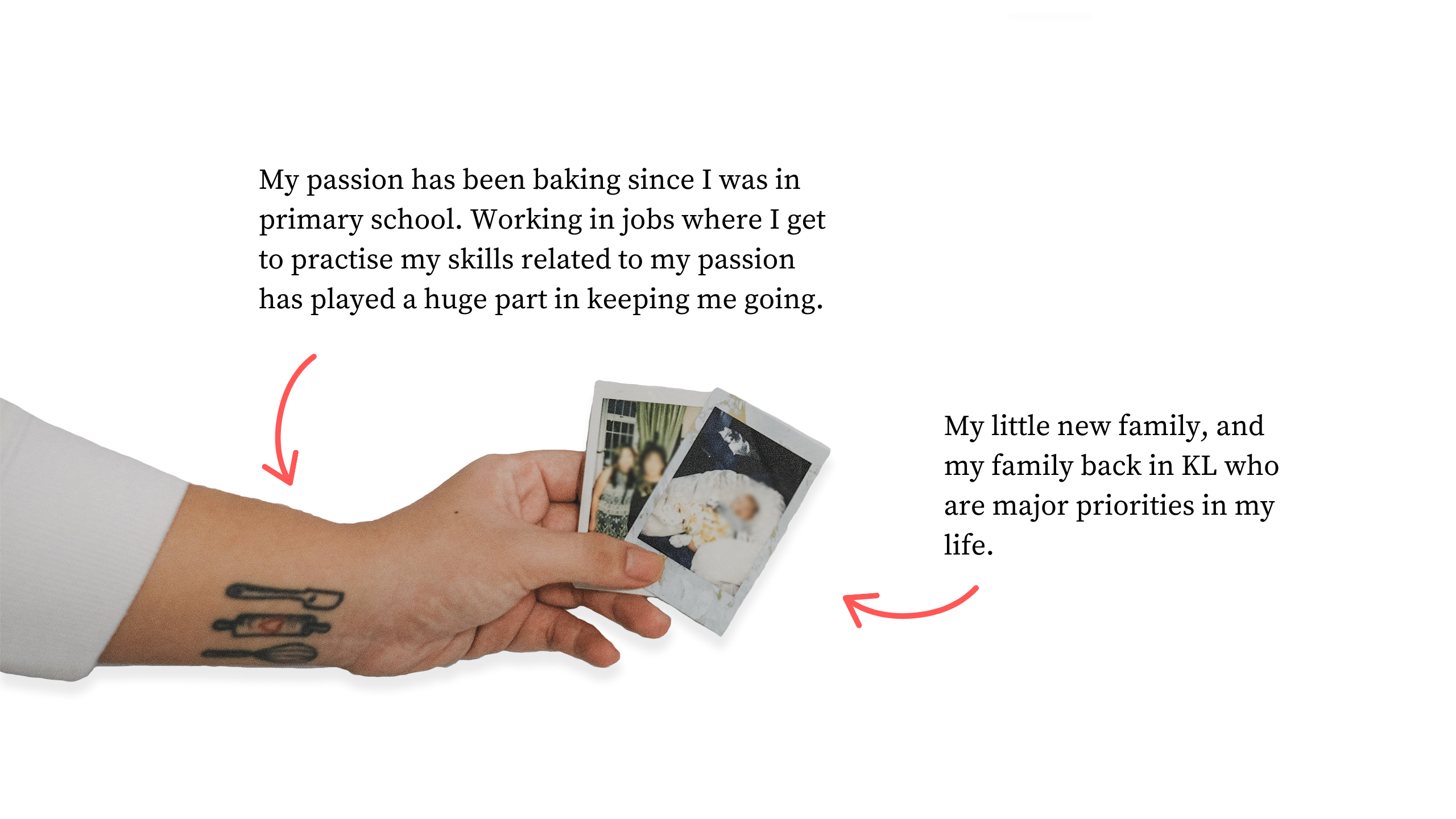

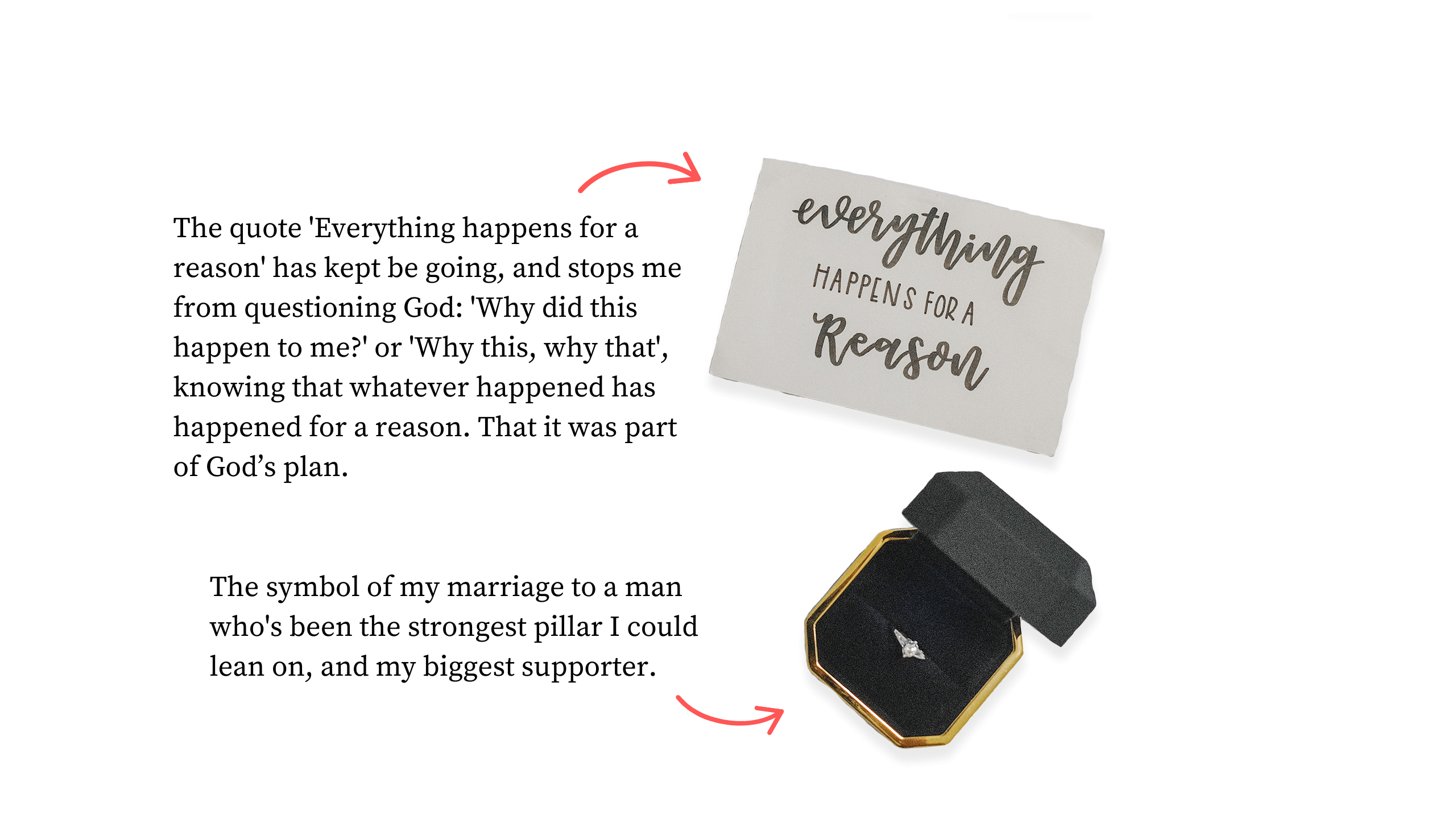

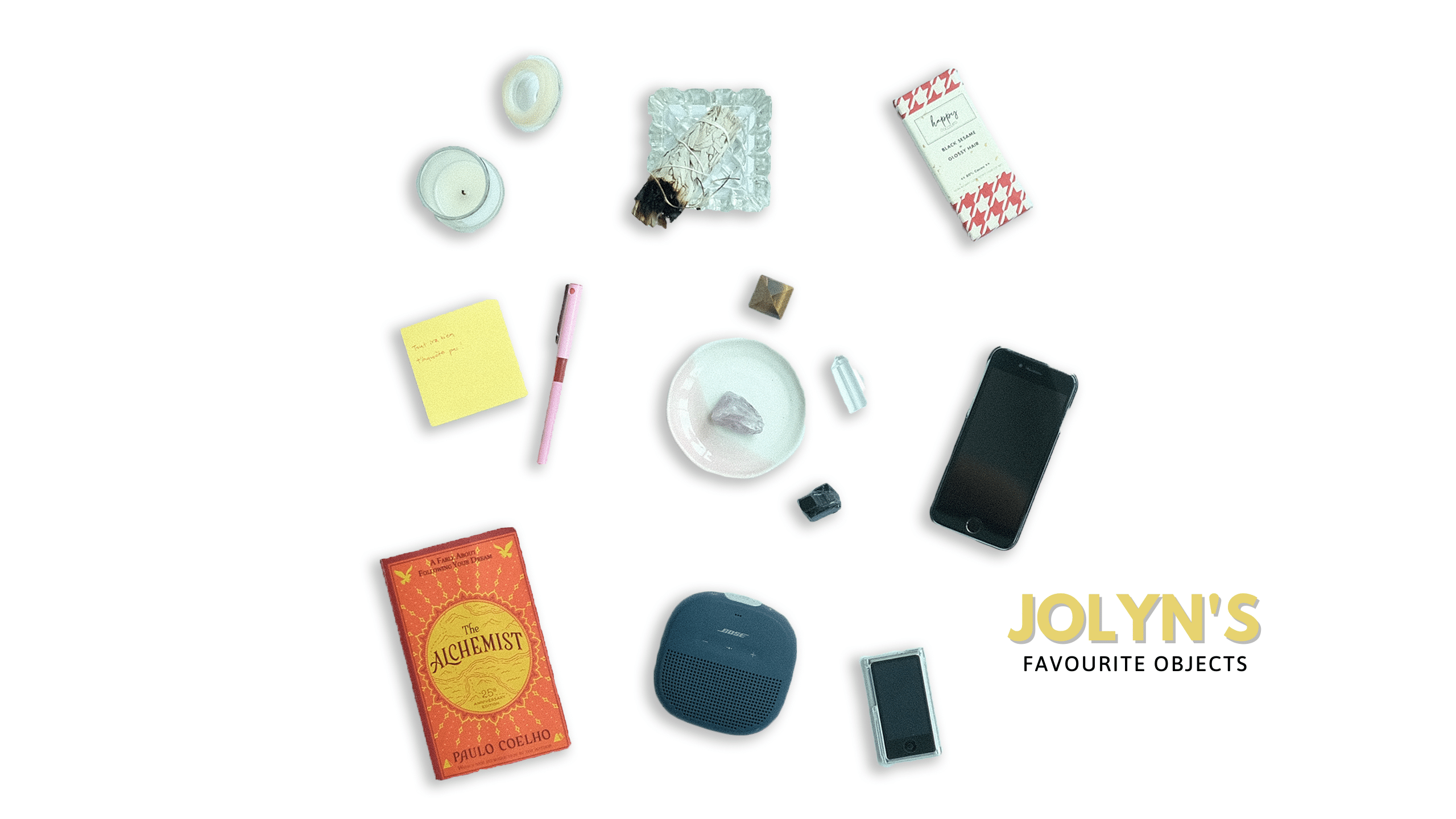

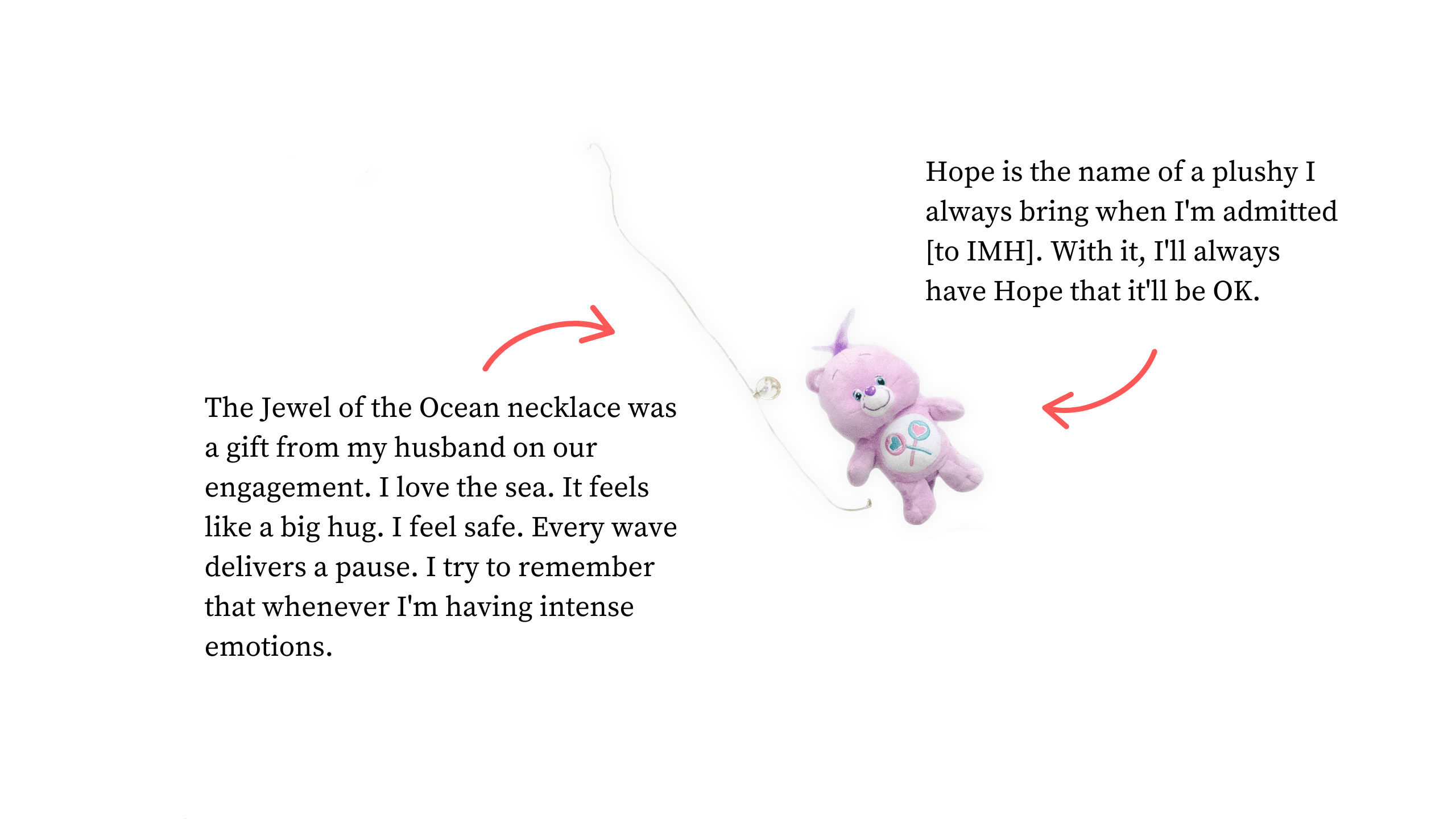

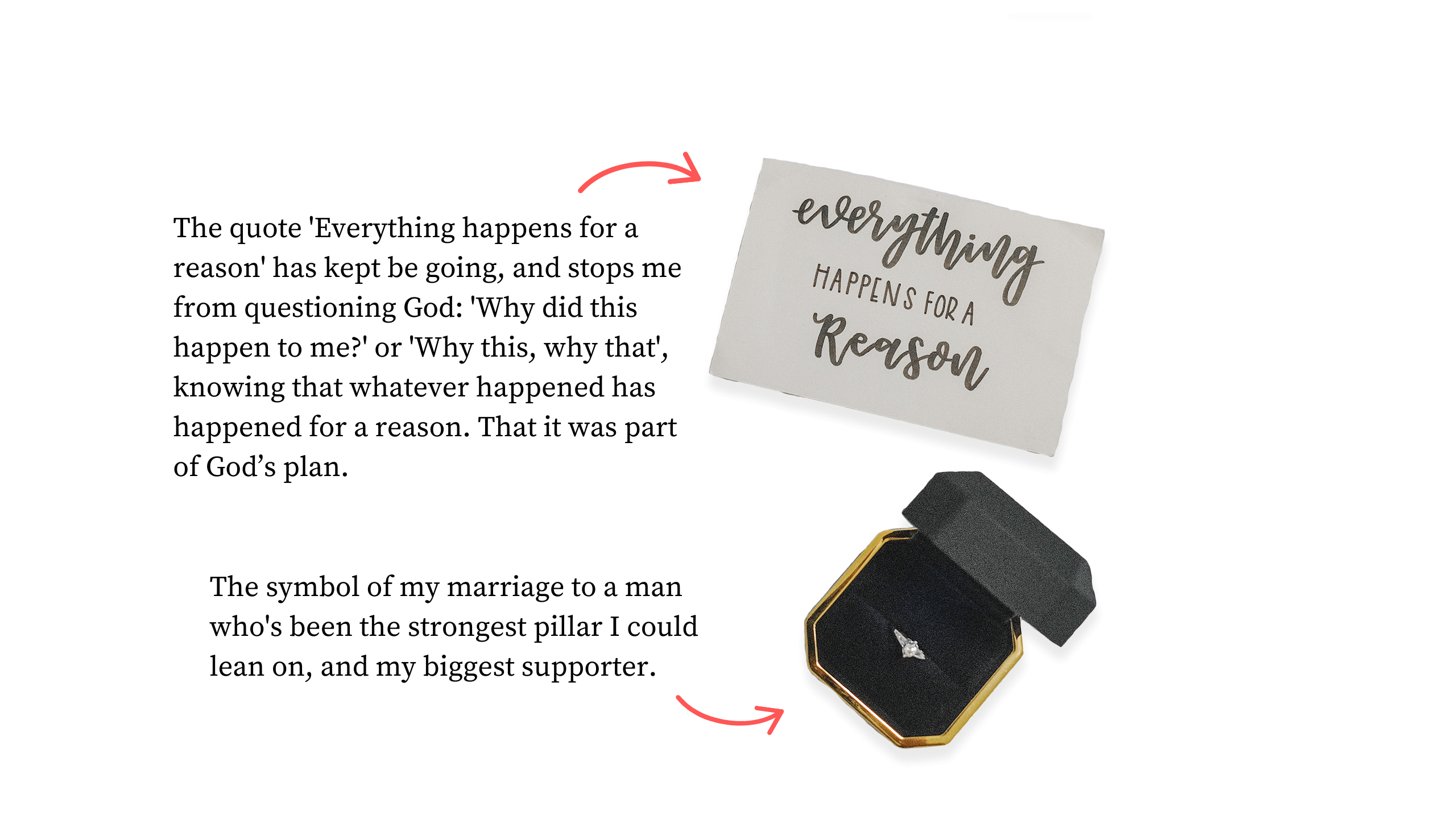

Click and scroll through to view the objects of sentimental value and importance to Jolyn, Mahita, Mano, Nicole and Shafiqah. And discover why each item holds significance in their lives.

Suicide is preventable, assures Dr Ng, but adds that it is dynamic and hence unpredictable.

"Different [people] have a different tolerance to stress at different points in time. An intervention that helps me today to cope with my stressors, may not help me next month. I could have a stress [event] that is so severe that even though I have low risk today, my risk will be higher next month,” he explains.

Oftentimes a person with suicidal ideation withdraws from those around them. By self-isolating, their world shrinks making it more difficult to get out of the rut, explains Dr Ng.

At this stage, he says it is important to be surrounded by loved ones and/or to speak to a professional, who is trained to break the cycle of cognitive distortions that can lead a person to believe there is no way out of their existing emotional state.

“Change is the only constant. To know that things would change, their perception of things would change, certain feelings also change. Things will get better with time.”

What to look out for?

Signs of suicidal ideation can be verbal and/or behavioural. For example, they might say how tired they feel and that life has no meaning. Sometimes they give away prized possessions and say goodbye to loved ones, or lose interest in hobbies. There may even be emotional outbursts.

“When people start saying these things, you should perk up and listen, in case you’re missing something,” emphasises Dr Ng.

Once the conversation begins, one must be prepared and willing to listen, he advises. “We cannot ask somebody, ‘Are you feeling okay? Do you have suicidal thoughts?’ And when they tell you, people cannot handle and don’t want to talk. That’s even worse.”

He warns against doing or saying certain things that might trigger the individual.

“If we give them certain responses, you may make them feel rejected, unheard,” he explains. “They took a lot of courage to open up. So we should not take that lightly.”

Despite the daily struggles of managing their suicidal thoughts and mental health conditions, all five have chosen to continue living. These are their reasons.

Mahita was just 20 years old when she met her future partner for life. She was “insecure and impressionable”, and him being 10 years her senior pushed her to grow up and mature.

“I came into my own once I got married and had children. I felt more secure,” she says, although having kids made her very tired all the time, which made her “quite angry”.

She explains that one of the symptoms of bipolar disorder is fatigue, which leads to the third turning point in her life, and also the biggest; being diagnosed. The knowledge that she had bipolar finally made sense of the way she was capable of behaving – being angry, obnoxious and lashing out at people.

Read instead

Meeting her husband, James, turned Nicole’s life around. With him, she felt secure, understood and loved.

“I thought things were gonna get better. But shortly after, my brother passed away and then my husband and I were trying for a baby and we had a miscarriage,” she shares.

“But my husband was there for me, and he was telling me that we will try again, and things will get better.”

All this while, the relationship with her family had also started to improve.

“The biggest responsibility as to why I have to continue living is that I am responsible for my baby's life. That's definitely a solid reason as to not ending my life.”

Read instead

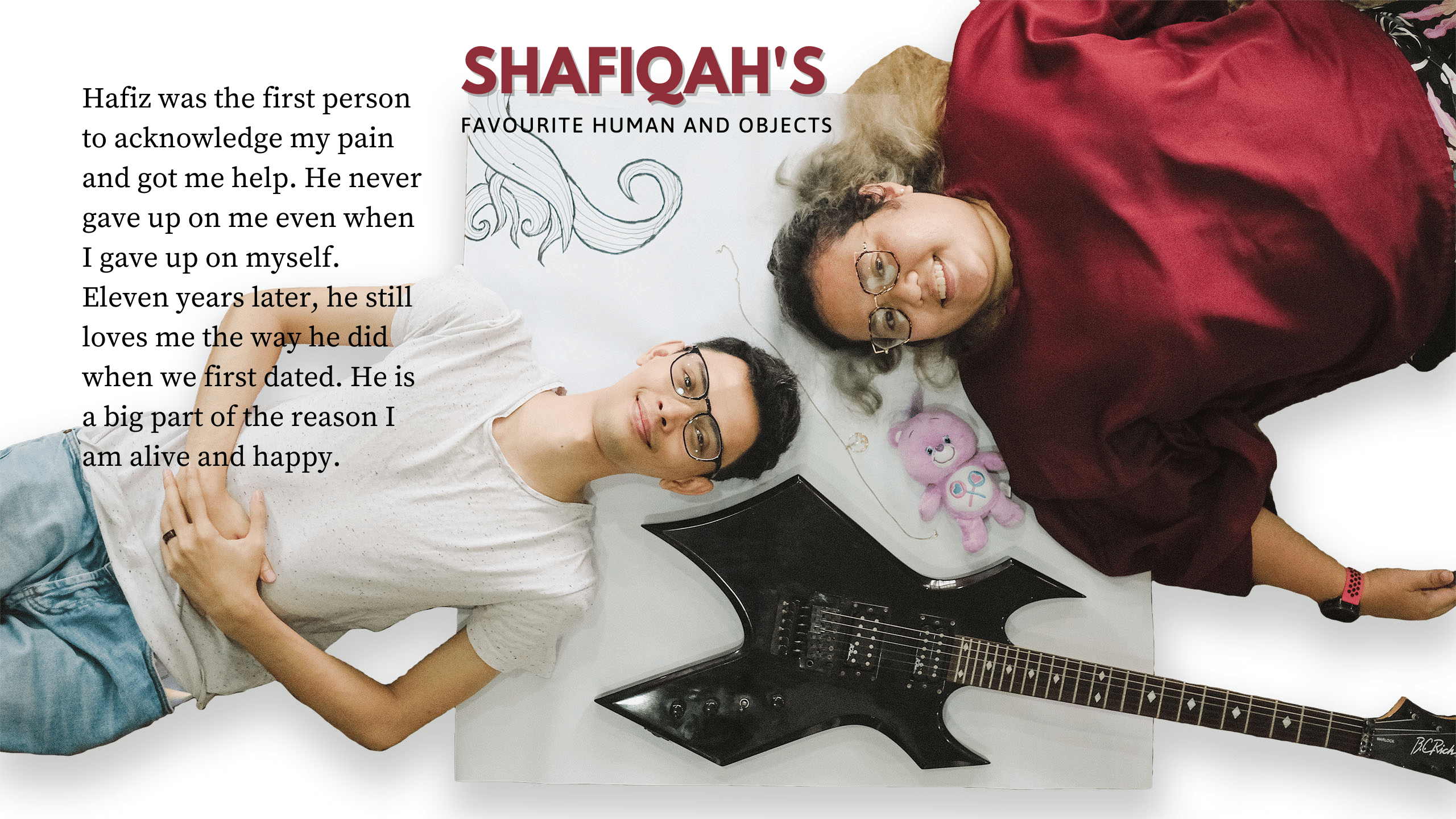

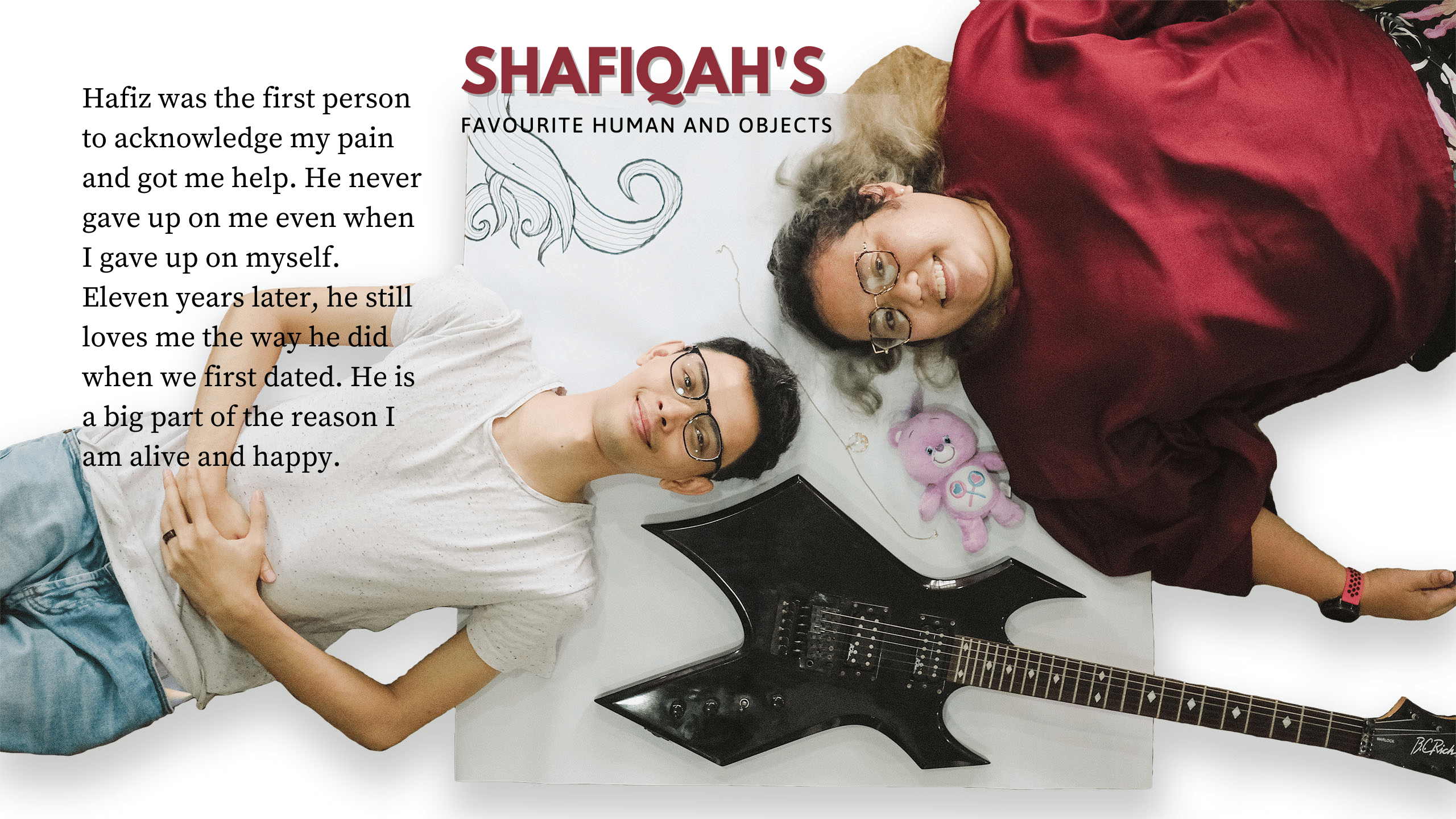

At 17, Shafiqah started to see the school counsellor – made possible by Hafiz, her then-boyfriend and now husband, who knew that she was struggling in school and self-harming more frequently to cope. She says that he was the reason for her recovery and why she has a better life.

When Shafiqah's parents learnt about her mental illness, they were surprised and shocked, but responded with love.

“My dad decided to embrace me and love me more. He wanted to show his affection. And that was pivotal for me,” she says. “My mum couldn't really understand it, but I could tell that she wanted to do something but she didn't know what to do.”

“I was so scared that my parents were gonna abandon me, because that was the thought process I had all along.”

After Shafiqah graduated from polytechnic and started work, her life took on a sense of purpose and fulfilment. “I started to feel like there was so much more I could do in my life,” she says.

Still, choosing to live has not eradicated Shafiqah’s decade-long battle with suicidal ideation. Her latest attempt on her life in February 2021 left her unconscious for eight days.

“When I woke up on the ninth day, I realised that there was something that I really never wanted to go back to. It allowed me to see that I don't want to die,” she explains.

Read instead

WATCH: Shafiqah tells us why her husband, Hafiz, is one of the main reasons why she started therapy, and is still alive today.

During his 44-day stay at IMH, Mano was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (schizophrenia plus a mood disorder), Type 2 bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety. A cocktail of medications has enabled him to function in daily life.

“For schizophrenia, I moderate my sleep better...eight hours every day. Never skip my medication… It blocks all the noises. For my mood, I'm taking another medication... I try not to be too excited, or too sad, just keep a balance, like waves in the sea. For anxiety, I try not to put myself into too anxious of a situation.”

“Among the things I learned is to keep calm,” says Mano, while also finding and addressing the root cause of his emotions, “That’s how I manage it [suicidal ideation]. You need to be kind to yourself.”

Being able to call someone and say, ‘I need to talk,’ has also been a lifeline, for Mano. But the support is mutual, and it is important to look out for friends too, he says, “When they are feeling low, I try to be there for them. So it's not just paddling the boat by yourself, it's paddling together to move forward.”

“You might feel it is completely hopeless, but what about the good times? It can't be all grey clouds, and no blue clouds at all. Right now, there's a storm happening. It will pass.”

Read instead

One of Jolyn's ways to navigate and live with the suicidal ideation is to channel her energy into her chocolate-making business. Retreating to her community for comfort has also been essential for her.

She has relied on two groups of people whom she turns to in moments of distress, friends and customers, each providing different ways to console her.

“One is my push-up bra, to be there to hold on to me. And the other is to be like a cheerleader... with pom poms to say, 'Go for it.’”

Read instead

WATCH: Jolyn discovers the emotionally healing properties of the chocolate-making process.

Support not stigma

Never underestimate the importance of support from both loved ones and strangers, of creating awareness and ending stigma in society.

Loved ones, friends and community have been essential in helping suicide attempt survivors to manage their suicidal ideation and mental health conditions.

But society too plays a significant role in determining the quality of life of those who continue to grapple with suicidal ideation.

Inclusivity can remain an elusive pipe dream for many who live with mental illness or mental health conditions; thwarted at every turn by the insidious prevalence of stigma and discrimination.

“I definitely felt discrimination, especially from my family, which is why I probably hurt more. And I wish for them and everyone else to be more understanding towards this,” reveals Nicole.

“It’s 2021, everyone knows that mental health is not to [be] joked about, and people should be really taking it seriously. That it can lead to death.”

Nicole wants to bring up her son, Jacob, in a loving environment that nurtures his self-esteem and self-worth.

Nicole wants to bring up her son, Jacob, in a loving environment that nurtures his self-esteem and self-worth.

In Singapore, one in seven residents will develop a mental health condition in their lifetime, according to a 2016 national study released by IMH. More than 75 per cent do not get professional help.

Without safe spaces, public awareness and acceptance, those who inhabit the margins where mental illness and mental health conditions are everyday realities, will continue to feel ostracised and invisible.

“Singaporeans are very critical and judge a lot on every single thing. If we place less of our own ideals on other people, it will definitely create a healthier environment.”

Says Shafiqah, “It’s so difficult to talk about mental health issues. Maybe depression and anxiety is a bit more accepted now, which is great. But I think a lot of other disorders and conditions are still very stigmatised.”

Take borderline personality disorder, or BPD, the disorder that Shafiqah was diagnosed with.

“When I say I have BPD, people think I have multiple personality disorder or bipolar. They immediately think that ‘you are this or that kind of person.’ But having a condition doesn't say what kind of person you are. It just shows what kind of things you go through in terms of your mental health,” she argues.

Shafiqah has faced discrimination due to her mental illness, and knows how important it is that those who live with a mental health condition are treated with respect and dignity. She volunteers to create more awareness around mental wellness and to eliminate stigma.

Shafiqah has faced discrimination due to her mental illness, and knows how important it is that those who live with a mental health condition are treated with respect and dignity. She volunteers to create more awareness around mental wellness and to eliminate stigma.

Other hurdles remain.

“It was hard to get treatment from a good doctor and to be warded in some of the psychiatric wards, because they think that patients with borderline personality disorder might be harder to handle.”

Cost is also a barrier; the form of therapy that is known to work well for BPD is not widely available in the public health system. If it were more affordable, she would sign up for it, says Shafiqah.

“It’s important to treat patients equally, because all patients deserve to be treated.”

Shafiqah suggests that people treat someone with mental health issues like people with a physical disability or health condition. “If someone couldn't walk, would you tell them to just walk; it's a matter of willpower? It's not possible,” she explains.

Despite an increase in coverage about mental health and wellness, and a rise in suicide deaths in Singapore, suicide remains a taboo topic. The silence often stymies efforts to create awareness and dismantle misconceptions. Silence also entrenches the obstacles that prevent people from seeking the support they need.

SG Mental Health Matters conducted a poll from March to April 2021 and found that nearly 80 per cent of its 561 respondents thought that not enough was being done to prevent suicide on a nationwide scale.

Dr Ng says the solution to end stigma is simply to talk about suicide. But he notes a reticence and reluctance to do so is due to a misguided fear that it will plant ideas into people’s heads.

There is also the long-held concern about the Werther effect, which shows a rise in copycat suicides after media reports on the issue.

Dr Ng says, “People don’t just think about suicide because they hear about it. The more people don’t talk about it, the more a child or an adult will feel shameful, embarrassed to bring up this topic.”

Living the shame of attempting suicide

Those who have tried to kill themselves are shamed or stigmatised. Often the people in their lives fail to understand or empathise, says Dr Rajesh and assume it was “a sign of weakness of their personality, or that they are not resilient enough to face life’s challenges.”

Dr Yeo notes that the stigma of suicide can lead to increased feelings of shame and guilt: “Mental illness, alcohol and drug use, and chronic medical conditions can also put [suicide attempt] survivors at a greater risk of suicide.”

Singapore has decriminalised attempted suicide, with amendments to the Penal Code taking effect on 1 January 2020. But more can be done to improve the availability of services to those who need it.

In particular, education, Dr Yeo believes, must start in schools: “So children not only gain awareness and understanding about such topics, but learn that suicide and mental health struggles can and should be discussed, rather than hidden away as shameful taboos.”

So why have these suicide attempt survivors decided to share their stories, at the risk of being stigmatised?

Photo courtesy of Mano Esperanza

Photo courtesy of Mano Esperanza

Photo courtesy of Shafiqah Ramani

Photo courtesy of Shafiqah Ramani

Photo courtesy of Jolyn Yong

Photo courtesy of Jolyn Yong

Photo courtesy of Nicole Voon

Photo courtesy of Nicole Voon

Photo courtesy of Mahita Vas

Photo courtesy of Mahita Vas

Taking it a day at a time

Having lived and survived attempts to take their own lives, Mano, Mahita, Jolyn, Shafiqah and Nicole share advice and their hopes for the future.

Given that stability is often a rare and sought-after state of mind for those who live with mental illness and other mental health issues, it might seem redundant to plan too far ahead into the future. That said, living in the moment does not necessarily rule out building structure around one's life, and making short-term plans, as Mano does.

While recovering at the hospital from her first suicide attempt, Mahita reveals that her husband had “extracted” a promise from her.

“Anything can happen, but I don't focus on what can happen to lead me to kill myself. I focus on, ‘’Wow, I’m going to see my daughter [who lives in England], because that's what I want to do.’ Yeah, it's day by day, because that's just how my mind works.”

For the longest time, Jolyn had harboured the thought that she would die at 30 years old. Now months away from reaching her third decade, she turned to cartomancy to gain insight into the future. The tarot card reader predicted that she would live years beyond her upcoming birthday, which she says came as a relief.

“It gave me a sense of reassurance [that] I could do things. And it gives me extra confidence in myself, and helped me cease all these suicidal thoughts.”

“Suicide is never a solution to a problem”, says Shafiqah. “It’s not going to fix your mistakes or issues.”

Instead she posits an alternative to thinking about “ending the pain” by suicide.

“I started to think about the joy I have, rather than the pain. Because even when we have all that pain, we still have that joy, even if a little. ”

Living through the ups and downs of being “super positive” and then “depressed” has taught Nicole the power of compassion and equanimity.

“Instead of being a super positive person or a super depressed person, I'm somewhere in between now, which is good, because sometimes average is good.”

But while the suicidal thoughts linger, Nicole tells herself, “‘No, not today, I'm too busy. I have a baby, a business, a husband to take care of.' To live with it is not as bad [as before]. I'm in a much better place with positive people around me.”

Read instead

At the end of the day, the only person to rely on is still oneself, which includes asking for help and advice if needed, advises Mano. “People can throw in the ropes, the ladder, but if you do not want to get out [of the dark hole], no one's gonna want to help you get out of there.”

“Experience the thing that you have to experience first. But then pick yourself up, because that's what I did for myself. Only you can bring yourself out of that dark hole.”

If you are thinking about suicide, or know someone who is, and want to seek advice and support, or simply to talk, please reach out to these helplines and resources in the region, or scroll down for those in Singapore.

Helplines and resources

- Samaritans of Singapore (SOS): 1-767 (24/7)

- IMH Helpline: +65 6389-2222 (24/7)

- National CARE Hotline: 1800-202-6868

- Agency for Integrated Care Hotline (for ageing, caregiving and mental health-related support): 1800-650-6060 (8.30am-8.30pm)

- Hear4U (WhatsApp service): +65 6978-2728 (Mon-Fri, 10am-5pm)

- TOUCHline (for youths): 1800-377-2252 (Mon-Fri, 9am-6pm)

- Tinkle Friend Helpline (for children aged 7-12 years): 1800-2744-788 (Mon-Fri, 2.30-5pm)

Contributors

Writer, Photography and Content Design

Tsen-Waye Tay

Producer and Video

Tan Pei Lin

Editor

Chris D

Illustration

Ng Shian

Executive Producer

Lin Yanqin

Special thanks

to Projector X and CRANE for providing locations to conduct Mano and Jolyn's interviews, respectively.