One Child, One Skill,

At a Time

A grassroots initiative in Singapore sets out to teach basic skills to children with autism. By engaging student volunteers, these sessions widen the public's understanding about living with autism. And with greater awareness, the ultimate goal is for society to become more inclusive and accepting of people who are differently abled.

When new parents Sandra Chan and Alex Toh discovered that their son Jeston was autistic, he was just two years and seven months old. The news was devastating initially, and it took them months to accept the diagnosis.

"After we realised that it was autism, I cried for four months every day, because the thought of him [Jeston] [having a] future at that time was zero. It was a total blank."

Jeston Toh at eight months. (Photo courtesy of Sandra Chan)

Jeston Toh at eight months. (Photo courtesy of Sandra Chan)

Two of Sandra's friends, a speech therapist and a psychology lecturer, had first alerted her to the possibility of Jeston having an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It was 2015, and their "casual observation" happened at a weekly Chinese co-op for home-schooled children. They noticed that Jeston had trouble interacting with kids his same age; he was either disinterested or preferred to play alone.

At 29 months old, Jeston is a few moons shy of being diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. (Photo by Sandra Chan)

At 29 months old, Jeston is a few moons shy of being diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. (Photo by Sandra Chan)

To illustrate what they saw, one of Sandra's friends shared a video that explained the early signs of autism. It exposed her to Jeston’s world and the possible reasons for his behaviour, such as poor eye contact, inability to manage his emotions, delayed speech and echolalia.

It was hard for Sandra and Alex to come to terms with Jeston being autistic. Says Sandra, “Every day, I would be asking God, 'What have I done wrong?’” She also recalls Alex saying that Jeston was too young to be labelled a 'problem child' and had hoped it might be a 'phase that would pass'.

In fact, as Sandra reveals, there were moments in the year after the diagnosis that she had fallen into a state of despair, often feeling depressed and at a loss as to what to do.

She says, it was the unconditional love for their son and "God's grace and love" that gave them the strength to persevere.

Teeth marks from when Jeston would bite his dad as a way to express his frustration when unable to verbalise his emotions and thoughts. (Photo by Sandra Chan)

Teeth marks from when Jeston would bite his dad as a way to express his frustration when unable to verbalise his emotions and thoughts. (Photo by Sandra Chan)

But things turned around when Alex suggested sending Jeston for speech therapy to improve his verbal, non-verbal and social communication. She calls it their "acceptance period", when Alex and her started to embrace the idea that their child might be autistic and to do something, rather than remain in denial.

The first step was bringing Jeston to a doctor, where he was diagnosed with ASD. Sandra and Alex then looked for a therapist. Since coming to terms with Jeston's diagnosis, Sandra and Alex have done everything to ensure he has the best start in life.

Jeston responded well to therapy and his intellectual development progressed steadily, which was a relief for his parents. Things were beginning to look up after having experienced an uphill battle getting to where the family is now.

Alex reads a bedtime story to Jeston and daughter, Jemmie. (Photo by Sandra Chan)

Alex reads a bedtime story to Jeston and daughter, Jemmie. (Photo by Sandra Chan)

"2016 was a very challenging period. Jeston couldn't express himself. He would scream, bang his head, or roll on the floor. Every day, you will hear your parents and relatives say, 'Why is he like that? Did you do anything wrong? What did you eat during pregnancy?' I almost fell into depression."

Situation in Singapore

In Singapore, one in 150 children has autism. This is higher than the World Health Organisation's global rate of one in 160 children. The worldwide prevalence for ASD is estimated at one per cent.

According to the National University Hospital of Singapore, at least 400 new cases are diagnosed each year. Experts have attributed the high incidence of autism in Singapore and the rise in numbers of people with autism to an increase in awareness and testing.

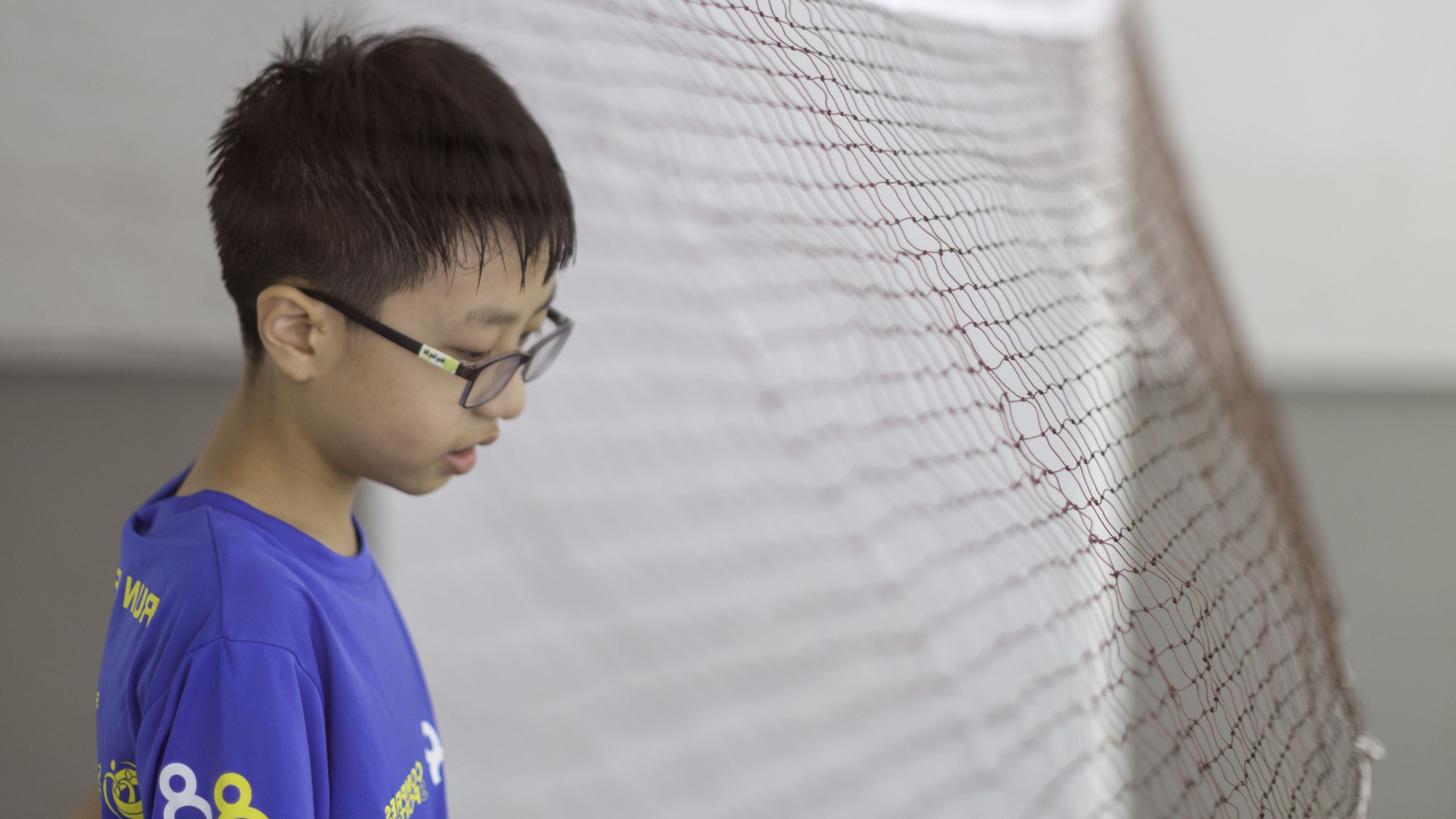

Photo by Tsen-Waye Tay

Challenges for caregivers

People with ASDs and their caregivers are often subject to stigma and discrimination. Due to their "impaired social behaviour, communication and language", parents of children with autism, like Sandra, say that being in public among strangers can be especially difficult.

Brenda Tan, who started One Child One Skill, is mother to 15-year-old Calder Kam, who was diagnosed with autism when he was three. Brenda says, "Communication is a very big barrier in making friends or mingling with people outside of the family."

"Emotional control is another issue. For my son, meltdowns were very common when he was small. That could be very stressful for the family."

Brenda on a trip to Taipei, Taiwan, with Calder and his younger sister Ethel. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Tan)

Brenda on a trip to Taipei, Taiwan, with Calder and his younger sister Ethel. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Tan)

Bringing him out was a "feat in itself,", Brenda adds. But since he loved being outdoors, so he could "run, flap his arms and jump around", she had to learn to ignore how people reacted to Calder.

"It would be great if society understood autism enough to see him behaving differently and be okay with it. Rather than look so alarmed...Especially when they have young kids and try to shield them from him."

Like many parents who first learn that their child has autism, Brenda felt lost, as if she were living "in a daze," unable to make sense of what the diagnosis meant for her son. Instead of letting it paralyse her, Brenda eventually decided that she needed to find out what her family was dealing with. This journey of discovery into the world of autism spectrum disorders led her to self-publish a book in 2010 of 31 accounts from other parents in Singapore who shared similar stories.

Brenda's first book opened readers to the world of families living with autism in Singapore. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Tan)

Brenda's first book opened readers to the world of families living with autism in Singapore. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Tan)

After the book came out, the former journalist continued to share her experience as a mother of an autistic boy to create more public awareness about the condition. In 2013, while giving a talk to a group of psychology students at a polytechnic in Singapore, one of them asked how they could help families like Brenda's. "Come teach our children," was her immediate response. With support from the lecturer, Dr Juliet Choo, to mobilise students as volunteers, One Child One Skill (OCOS) was initiated later that year and continues to take place during the semester breaks at participating tertiary institutions, like the National University of Singapore.

"Families want a befriender. Somebody to know our child better, help the child learn a skill and give some respite to the caregiver. The most important thing is that they've seen the difficulties the family faces. And this increases their empathy."

Calder cycling with his mum and Ethel. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Tan)

Calder cycling with his mum and Ethel. (Photo courtesy of Brenda Tan)

One Child One Skill's (OCOS) primary goal is to match students to families who have children with autism. Parents also choose a skill that volunteers can teach their child, for instance to help with socialisation and hand-eye co-ordination. They also play with the child.

"You would think that the parents could teach these skills to their child, but often, the parents are so drained providing the basic necessities and helping the child with schoolwork."

The community-led scheme has been very popular. Brenda says demand usually outstrips supply, where more parents sign up than there are volunteers available to be matched to each family.

Since its inception, OCOS has reached out to nearly 300 children through more than 600 student-volunteers.

Brenda recognises that it can be challenging for students at the start when they first meet a person with autism. She says the misconception is that these children are "not reachable" and that they are from "another world" and are "impossible to teach." She says that "teachability" is very important when deciding to volunteer or not.

"You have to be adaptable and resourceful teaching children with autism. It's not as simple as giving tuition."

Sandra is one of the hundreds of parents who have benefitted from One Child One Skill. Even though Jeston attends speech therapy classes, she signed up for volunteers to help develop his interpersonal skills. Jeston meets his new friends Mitchell and Qiwei for the first time and quickly warms up to them.

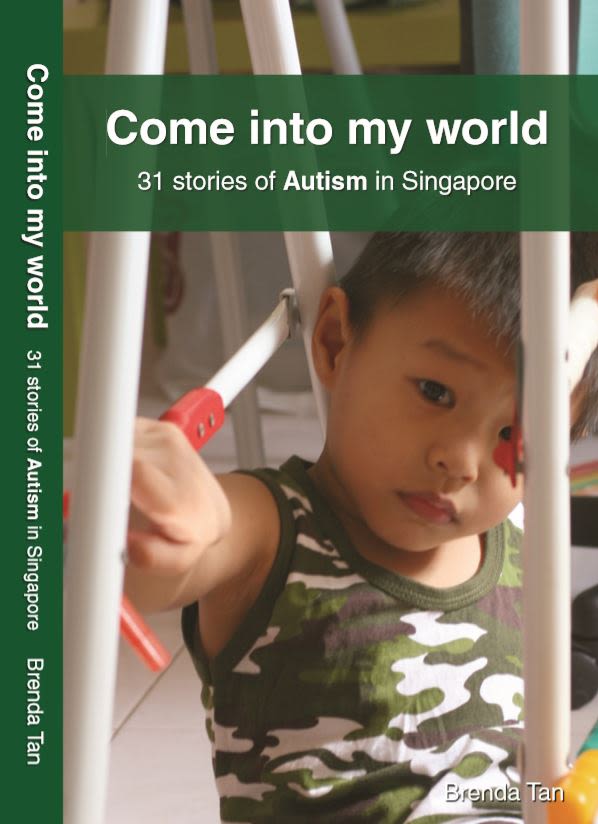

As Sandra watches them over the nanny cam, she jots down her feedback. These notes give the interactions structure and suggest areas for improvement.

Sandra has requested that the volunteers teach Jeston to play board games. They work in pairs and spend 1.5 hours each week over eight visits.

"Let's say you are teaching him a certain skill, he may only apply it on you, but when it comes to a different situation, he cannot apply it at all. So generalising with different people, besides mummy and daddy, is very important."

Volunteers like Mitchell bring in a variety of play to these sessions and can expose a child with autism, like Jeston, to different degrees of interaction.

Volunteers like Mitchell bring in a variety of play to these sessions and can expose a child with autism, like Jeston, to different degrees of interaction.

Sandra, too, took matters into her own hands, conducting interventions at home using methods picked up through self-study and attending courses. They had several breakthroughs, she says, allowing her to reach out to Jeston in deeper, more constructive ways.

Cheerful and friendly, Jeston often leads playtime at home, as more reserved volunteers like Qiwei watch on.

Cheerful and friendly, Jeston often leads playtime at home, as more reserved volunteers like Qiwei watch on.

"I learnt the techniques of how to connect with my child, and how to help him. And then I did my own intervention with him through play. Jeston has shown me he's able to learn. It’s a matter of finding a way that works for him. "

Besides being naturally gifted at the piano and being obsessed with lifts, another of Jeston's passions is his love of trains.

Besides being naturally gifted at the piano and being obsessed with lifts, another of Jeston's passions is his love of trains.

Heng Wei's parents first learned he was autistic when he was two years old. His father, Wong Sang Min, explains that his learning and speech difficulties are the main obstacle to understanding simple instructions.

"We have to repeat what we say many times. It's a very slow process. We learned that we have to be patient and that it's good to have a support group to encourage and help each other."

Parents can often find themselves overwhelmed with taking care of children that have special needs. Many lower-income families might not be able to afford to hire live-in help to lighten their responsibilities or pay for speech and occupational therapy sessions.

What One Child One Skill provides is a reprieve from the 24/7 care that children with an ASD might require. Even if just for an hour or so each week.

"One positive aspect of this programme is that it gives caregivers free time," says Sang Min. Though he says he wished the programme lasted longer than the eight weeks: "If we can make it a year-long initiative that will definitely give the caregiver more time to take care of themselves."

This will not be possible, however, since the One Child One Skill initiative takes place during the students' tertiary school holidays. The end of the eight session usually marks the start of the next school term for volunteers.

"He is quite a mild-mannered child. He seldom has meltdowns. He likes to play with children. The only challenge is he doesn't know how to communicate. A lot of times he is a bystander."

Having volunteers from One Child One Skill spend time with Heng Wei has also made a huge difference to his growth. Besides learning new skills that keep Heng Wei physically active, Sang Min and his wife, Yeng Ching, signed up because they wanted to expose their son to strangers.

Learning to throw balls of different sizes can help Heng Wei build his motor skills.

Learning to throw balls of different sizes can help Heng Wei build his motor skills.

Learning to play sport has built Heng Wei's self-confidence. "What we see is that he needs a lot of encouragement," says Sang Min. "And he really enjoys working with the volunteers...That's why this is a very good initiative and I want to promote it to more people."

"After the programme, he's more expressive. He knows what he likes and is able to articulate what he wants. During the weekends, he'll request, 'Let's go play ball.'"

Essential to Heng Wei's development is finding what he likes doing and enabling him to explore and build on these interests. For instance, Sang Min says Heng Wei enjoys watching food-related programmes and his mother cook. Hence, Sang Min thinks this could be a career path for him. "It's going to be difficult for him to work for people," explains Sang Min. "So given his interest in cooking, we want to train him to either be a chef or an assistant to a chef."

"It's important to identify what your child is good at and build on those skills. They can use it to support themselves in the future."

Heng Wei enjoys cooking and assisting his mum, Yeng Ching, in the kitchen. (Photo by Sang Min)

Heng Wei enjoys cooking and assisting his mum, Yeng Ching, in the kitchen. (Photo by Sang Min)

Still, Sang Min and Yeng Ching share a nagging worry with parents who have children with autism - what happens as they grow older and are no longer able to support their child? One solution is ensuring that they have friends and this means being part of a support group for families who have children with special needs.

"It's important that they have friends with similar traits," says Sang Min. "We want them to know there are people they can turn to when they need help. [And ] hopefully build some lifelong friendships."

Part of establishing a safe and inclusive future for Heng Wei and other children with autism is societal acceptance. This, Sang Min thinks, will take time and involves educating the public in Singapore.

“The most important thing with special needs children is patience. You need to understand them. You need to give them time. But everybody is rushing for time.”

Volunteers Low Xi Zhi and Ajeya Mantri set up the void deck for different types of games using balls.

Volunteers Low Xi Zhi and Ajeya Mantri set up the void deck for different types of games using balls.

Parents like Sang Min agree that One Child One Skill can encourage greater awareness by exposing more young people to autism and the families affected by it. This can eventually shift negative perceptions, correct stereotypes and end discrimination against people living with an ASD.

"People are self-centred and the pace is too fast [in Singapore]. Unless society is willing to slow down, or become more relaxed, it's going to be difficult for people with autism to be accepted."

"As a university student, it can be hard to devote time to this, but I enjoyed the sessions and it allowed me to de-stress and have fun. I also think Heng Wei had a good time and learned some simple skills, so it was a heartening experience."

A second-year mechanical engineering undergraduate at the National University of Singapore, Ajeya says that he has always enjoyed volunteering, especially for causes related to young children.

Since Heng Wei's parents wanted volunteers to work on his motor skills, Ajeya and Xi Zhi spent most of their time playing sports with him, such as basketball, soccer and catch. And although Heng Wei was slow to warm up, he eventually started to have a lot of fun in later sessions.

Heng Wei is challenged to a game of catch with Ajeya and Xi Zhi.

Heng Wei is challenged to a game of catch with Ajeya and Xi Zhi.

"It showed me how the sustained efforts of parents and other carers can make a huge difference in the development of a child."

Although Ajeya had read a lot about children with autism and interacted with a few kids as a camp facilitator and counsellor, it was his first time spending a sustained amount of time with an autistic kid. What impressed upon him the most was Heng Wei's pace of development.

Says Ajeya, "The major challenge was probably communication, as he spoke in simple sentences and was easily distracted. But with incredibly supporting parents, they [the parents] helped to adjust our teaching techniques to suit him [Heng Wei] best."

"Heng Wei has taught me to see every individual for who they are beyond the labels, to get to know their story and their dreams and empower them to own it."

Computer Engineering undergraduate Xi Zhi found the volunteering experience unique, because she developed a "real friendship" through her weekly play sessions with Heng Wei. She believes that by "truly" caring for him, empathy came naturally.

Adds Xi Zhi, "Because of my friendship with Heng Wei, I have become very comfortable in advocating for and interacting with people with autism."

"Once they understand how he communicates, the rapport between the volunteers and my son actually improved. Every week my son looks forward to spending time with them."

Kicking the ball can result in hours of fun, while strengthening Heng Wei's reflexes at the same time

Kicking the ball can result in hours of fun, while strengthening Heng Wei's reflexes at the same time

Volunteer Xi Zhi encourages Heng Wei to reach up and jump to develop his motor skills.

Volunteer Xi Zhi encourages Heng Wei to reach up and jump to develop his motor skills.

Ajeya recommends students sign up to volunteer with One Child One Skill. He says that the time spent with the child can contribute to their development.

"This also takes some of the load off the parents and motivates them to keep providing the highest level of concern for their children, knowing that others in society will care and support their children."

Despite the challenges of bringing up a child with autism, parents like Sandra and Alex have managed to build a strong and loving home for Jeston, with the support of family, friends and their community.

Sandra teaches Jeston to help out with chores at home, because she wants him to learn to be independent. (photo courtesy of Sandra Chan)

Sandra teaches Jeston to help out with chores at home, because she wants him to learn to be independent. (photo courtesy of Sandra Chan)

"He's a very joyful boy, independent and helpful. For kids [with autism], their emotions are very real. They just show [how they feel]. They don't have anything hidden."

Now at seven years old, Jeston is better able to express himself, in terms of explaining what he does or does not want. But Sandra notes he still finds it hard to describe his emotions.

He is also a great help around the home, having learnt to put away his clothes, toys and shoes. Jeston even bakes and chips in with the household chores, washing his own clothes, to "build his hand muscles and improve his writing," explains Sandra.

He also has a two-year-old baby sister, Jemmie, to cuddle and care for. Sandra says that after Jeston, they had not considered having a second child "for the longest time" and it took "courage" to take that step.

Jeston out and about with his baby sister Jemmie. (Photo courtesy of Sandra Chan)

Jeston out and about with his baby sister Jemmie. (Photo courtesy of Sandra Chan)

"It's great to have Jemmie, because we started to see another side of Jeston. He would talk to her very gently. So different from the boy who used to hit, bite, scratch and pinch people."

"With One Child One Skill, the purpose is not just about the students coming over and what they can do for the child. Rather it's also what the child can teach the students. It's a two-way thing."

Spending time with the volunteers has made Jeston more comfortable interacting with strangers. Soon enough he starts singing a song to volunteers Mitchell and Qiwei.

Spending time with the volunteers has made Jeston more comfortable interacting with strangers. Soon enough he starts singing a song to volunteers Mitchell and Qiwei.

With volunteers playing with Jeston, Sandra has a moment to herself, a rare thing for caregivers.

With volunteers playing with Jeston, Sandra has a moment to herself, a rare thing for caregivers.

Find out more about autism

An ex-journalist and mother to 16-year-old Calder who is on the spectrum, Brenda has written two books on autism to help people understand it better. While 'Come Into My World: 31 Stories of Autism' voices the hopes and fears of families in Singapore living with autism, 'My Way: 31 Stories of Independent Autism' chronicles the lives of working or married autistic adults from 15 countries and their journey towards independence. Both books are available at www.come-into-my-world.com

CONTRIBUTORS

Bob Lee

Photographer & Video

Tsen-Waye Tay

Producer, Writer & Content Designer

Christopher Annadorai

Executive Producer